The Australian Catholic University (Sydney Campus) is hosting a conference on Sacred Silence in Literature and the Arts, set for 4–5 October. Details here.

Author: Jason Goroncy

Joel McKerrow & the Mysterious Few – Welcome Home

℘℘℘℘

Joel McKerrow is a writer, speaker, educator, creativity specialist, and performance poet. He also lectures at Whitley Theological College in Melbourne, on Wurundjeri land.

Relics of war

The Great War presented clergymen with the ultimate test of faith; reconciling the benevolence of God with the greatest conflict in modern history. Killing on a grand scale would seem at odds with Christian fellowship and moral rightness. Most AIF chaplains believed the war to be just, the Will of God, King, and Country, part of God’s redemptive plan. Christians put an emphasis on the love and mercy of God, so the idea of God as warrior can seem difficult to reconcile.

The experience of army chaplains is well recorded – selfless service in very difficult conditions; coping with death, wounds, grief, and sorrow on an unprecedented scale. Churchmen provided spiritual consolation to the men as well as assisting with the wounded, boosting morale, providing entertainment, burying the dead, and writing to families.

In the same way as the men who served in the trenches, chaplains could not have returned to parish life unchanged. Dead sons, fathers, uncles, and brothers were not repatriated to Australia for burial and so churches became the important place to commemorate the conflict and honour the lost. Even in our increasingly-secular nation, Anzac Day ceremonies have an undeniably religious element, uniting people of different denominations for one day of remembrance.

As a Master of War Studies candidate of UNSW ADFA, I am writing my thesis on war relics in Australian churches. There exist already excellent works on memorial windows and honour boards in churches; I am focusing on artefacts or relics directly connected with the Australian experience of war that churches hold.

My interest began in Canberra – at the Warrior Chapel within St Andrew’s Presbyterian Church, Forrest. Rev Dr John Walker served as an AIF chaplain in World War One. Five of his children also served, and three sons were killed. Walker conceived the idea of embodying within the church a fitting tribute to the memory of parishioners who had given their lives in the Great War. Two communion chalices are used alternately in chapel services held on Anzac Day and Armistice Day – a silver chalice used on the Western Front by Chaplain Captain Percival Hope, and a small brass chalice used by Chaplain Rowan MacNeil while a prisoner at Changi.

I have asked just over 2000 Australian churches if they hold war relics within their buildings. The vast majority, of course, do not. But 2.75% do hold extraordinary and sometimes surprising relics. Grave markers, crosses, flags flown in battle, portable altars, communion linens from Nui Dat, Lae, and Palestine fit comfortably within the church fabric.

I have identified many churches where highly polished artillery shell vases are used for floral displays. Were they simply tokens of remembrance brought home as souvenirs? What memory did chaplains seek to evoke?

Millions and millions of artillery shells were fired in the First World War. Artillery was the biggest killer and provided the greatest source of war wounded. A very beautiful baptismal ewer at Grafton was crafted from a First World War artillery shell. Was this simply practicality or symbolic of new life at baptism received from something designed to kill?

All bar one of the 55 churches identified contain First and Second World War relics. Yet the tradition continues. At the Kapooka Soldier’s Chapel in Wagga, where raw army recruits are trained, a wooden crucifix contains metal from an armoured vehicle in which an Australian soldier in Afghanistan was travelling when he was killed.

It is easier, perhaps, to understand how some chaplains and soldiers brought souvenirs home from ruined churches; shards of broken church windows were gathered in ruined French and Belgian towns by an Anglican chaplain in the First World War and brought home to his parish. He had them made into windows that still bring the light into St John’s Reid. Candlesticks, chalices, patens, statues were all gathered from the rubble of destroyed churches on the Western Front and reinstalled in Australian churches in city and country.

Several churches have a ‘Blitz’ piece of St Paul’s Cathedral and All Hallows in London, Coventry Cathedral, and other English churches, sent out as tokens of gratitude to far-flung churches of empire who had contributed financially to their rebuilding after the Second World War.

I am not trying to simply document these relics but to understand why they were brought back, how they evoke memory and the stories behind each relic. I will also attempt to understand the religious nature of our commemoration, and the interconnection between war and Christianity. The relics may present an important perspective on the Judeo-Christian [sic] God as a warrior. One relic defies time; olive cuttings taken by a Light Horse chaplain at Gethsemane still flourish in the grounds of Our Lady Help of Christians, Ardlethan.

℘℘℘℘

Emily Gibbs works art the Australian War Memorial and is conducting research into war relics and religious faith. She can be contacted by email.

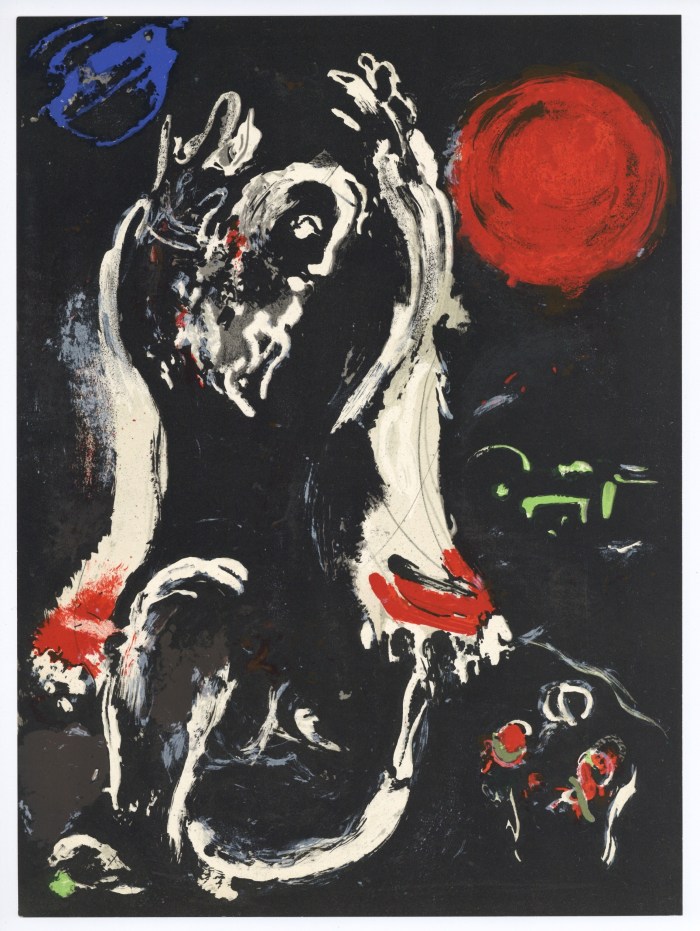

An Aged Isaiah Remembers

℘℘℘℘

CHRIS GREEN IS PROFESSOR OF THEOLOGY AT SOUTHEASTERN UNIVERSITY IN THE USA. HE IS THE AUTHOR OF SEVERAL BOOKS, INCLUDING SURPRISED BY GOD AND THE END IS MUSIC, BOTH PUBLISHED BY CASCADE PRESS. HE IS ALSO A VISUAL ARTIST.

Idris Murphy – Empyrean

Here, Idris Murphy introduces us to his upcoming exhibition of paintings – a luminous mystical response to the stark presence of the desert landscape, a meditation that invites theological and philosophical responses to the mystery we feel in a sense of place.

The Visual Commentary on Scripture

A new and dynamic online resource – The Visual Commentary on Scripture – has recently been launched by a team centred at King’s College London that is providing resources for those interested in the visual interpretation of the Bible, including general readers, scholars, preachers, and study groups. The project draws on diverse scholars in art and religion from around the world and will eventually build a library of up to 1500 commentaries that give a visual insight into the Biblical tradition. Each entry is curated like a small exhibition, and provides three key images that offer visual insight into a given passage. A longer overview is then provided where we both read and see the various insights into the process of understanding the meanings contained in a passage.

The project team is led by theologian Professor Ben Quash of King’s College who here offers a helpful introduction to the value of the project:

This unique project demonstrates the value of the visual arts in expanding our means of understanding, and our response to texts and their interpretation. There are currently over 80 completed commentaries now available on the website.

Professor Ben Quash explains that the project offers three main purposes:

First, it seeks to instruct those with little knowledge of the Bible about its contents. We hope this will be part of the strategic ‘impact’ of this project.

Second, it uses the warrant of the incarnation to affirm that physical sight can be a pathway to spiritual insight.

Third, the VCS aims to refresh viewers and engage their affective responses as well as their intellectual ones, affirming that images are made ‘to be gazed upon, so that we might glorify God and be filled with wonder and zeal’.

The Visual Commentary on Scripture is an exciting development. It is a richly-engaging resource that has been made easily accessible. It will be a valuable resource to students of the Bible, and those who teach and reflect on its ongoing relevance and authority. Bringing the world of the visual arts into this process of interpretation heightens an awareness of the lived experience of the biblical world as well as our own contemporary context. It allows for a renewed valuing of the visual arts as a means of accessing the world of the biblical tradition in conversation with the current horizon of our lives.

℘℘℘℘

ROD PATTENDEN IS AN ARTIST, ART HISTORIAN, AND THEOLOGIAN INTERESTED IN THE POWER OF IMAGES. HE LIVES AND WORKS ON AWABAKAL LAND.

Stations of the Cross, 2019

I had seen an exhibition of the New Zealand artist Colin McCahon in which he featured the Franciscan Stations of the Cross. I knew nothing of that tradition, and one Easter, as an Easter discipline for myself, I decided to ‘pray’ the Stations of the Cross by painting my own series. It dawned on me, slowly, that this exercise was an existential prayer. How do we live when we know that we are mortal? How do we live when we know that we are finite? How do we live when we experience suffering?

That led us in 2007, at St Ives Uniting Church in suburban Sydney, to try something new. We invited 15 leading artists to participate in an exhibition. Each would be allocated a different station, randomly, and would have 9 months to work on a response. I wrote a ‘pastorally informed’ commentary on each of the traditional Franciscan stations (14 plus ‘resurrection’), and that commentary became the brief for the artist. I tell artist’s that I am not looking for illustration of the story; more, I am looking for their engagement with the questions the station raises for them.

We have been doing it ever since. After I retired, we decided to do it at Northmead, where the church works with the Creative and Performing Arts High School, and we have shown the work at ACU Strathfield and at the Australian Centre for Christianity and Culture in Canberra.

When I approach artists, I ask them not because they are religious or not religious, Christian or not Christian; I ask them because they are good artists who have the capacity to address significant existential questions through their art.

Each year when I receive the works for the exhibition, I am excited by the artist’s integrity, and their capacity to give us works that reflect the deep questions of being. My background is as a pastoral theologian, and I see lived experience as primary text for theological reflection.

Each year we have large numbers of people walk through the exhibition as part of their Easter discipline, or ‘just out of interest’. Always, people are deeply moved; it is not unusual to see people with tears running down their faces, or, to hear them say, ‘I can identify with that’.

Last year, a teacher at a local Catholic Primary School taught a special unit to her grade 5–6 class on religious art through the first semester. She had one of the artists address her class at school, and brought 47 kids who pressed their noses against the art works, and who listened and looked with engaged interest. They went back to school and made their own ‘religious’ art works, and later had a wonderful exhibition of them. This year, that teacher will bring the staff of the school for a staff meeting at the exhibition and they have asked for a talking tour of the work.

We now have a number of events associated with the exhibition: the formal opening, a wine and cheese night, a jazz night, a Good Friday service, a grief workshop, a number of guided tours, the moderator of the UCA will offer a retreat for ministers and key leaders, and, most especially, an Eremos led a quiet half day. Our hope is to build the idea of groups of people making an Easter pilgrimage in which they might walk the way of the cross where there is a contemporary reading of Jesus walk.

You can access the catalogue here. The catalogue includes the commentary or brief given to the artists, images of all the art works, and some comment on the process of making the works by the artists.

Station 11: Jesus is nailed to the cross

Artist: Harrie Fasher

Artist’s comment: I have a spiritual connection to the earth, and find great solace walking and drawing in the landscape. The work I presented for the 11th station, Christ being nailed to the cross, is a steel study of a dead lamb, an Indian offering washed up from the ocean, and a study of feet nailed to the wall. The lamb, soft yet lifeless, represents purity and the earth. I built it in steel, a hard cold material that has been imbued with the properties of life lost. The offering was collected in India for its shape and texture, it holds memory of colour, ritual, and life. And the drawing is a literal representation of the station, feet nailed, produced by the meditative action of looking. Together the three works contemplate what such a sacrifice symbolises in our contemporary society.

Station 9: Jesus Falls the third time

Artist: Blak Douglas

Artist’s comment: So really my knee-jerk response from the outset was to paint a large cross in a landscape filled with Grass Trees (‘Black boys’) yet the cross has been hit by three large spears. Perhaps accompanying words are to the following effect. This piece personifies my lifelong frustration of being wrongfully encouraged to embrace the religion of colonialism and white suppression. From being ‘christened’ Adam Douglas Hill and registered ‘Church of England’, yet being only three generations removed from my tribal Dhungatti peoples. Having to participate in scripture on Tuesday mornings in Primary School or face the cane. Witnessing successive patriarchal governments be sworn in on King George’s bible, feigning honesty, and professing to uphold sound governance on a stolen land. This image – ‘Three strikes & you’re out’ – is metaphoric of how I’d like to see the illegal dominant faith upon this continent fall.

Station 14: Jesus is laid in the tomb

Artist: Jo Braithwaite

Artist’s comment: In this image, I battled to create an image that I hoped would reflect optimism through solidarity.

℘℘℘℘

DOUG PURNELL IS A PASTORAL THEOLOGIAN WHO IN HIS RETIREMENT IS FOCUSING ON A COMMITMENT TO A FULL-TIME STUDIO PRACTICE OF PAINTING THAT EXPLORES THE NATURE OF ABSTRACTION AND MARK MAKING. HE WAS FOR 17 YEARS THE DIRECTOR OF THE BLAKE PRIZE FOR RELIGIOUS ART. HE LIVES AND PAINTS ON GADIGAL LAND.

Healing/Wounding

By his wounds

You have been healed.

By his healing

You have been wounded.

By his wounds

You shall be wounded.

By his healing

You shall be healed.

By your wounds

He has been wounded.

By your wounds

You shall be healed.

℘℘℘℘

CHRIS GREEN IS PROFESSOR OF THEOLOGY AT SOUTHEASTERN UNIVERSITY IN THE USA. HE IS THE AUTHOR OF SEVERAL BOOKS, INCLUDING SURPRISED BY GOD AND THE END IS MUSIC, BOTH PUBLISHED BY CASCADE PRESS. HE IS ALSO A VISUAL ARTIST.

Before Good Friday

A few years ago, just before Easter, I pulled into the supermarket carpark. It was mid-afternoon on Maundy Thursday, the day before Good Friday. I had been stuck in a one-way back street behind a truck revving impatiently. It was not the ideal lead-up to my observance of Easter.

Through my car radio came the mellifluous tones of Lucky Oceans’ afternoon show on Radio National. Lucky introduced an album by Sam Baker called Pretty World. The back-story is that Baker was in Peru in 1986 on a train blown up by the Shining Path Maoist group. He was forced to witness the death of a 14-year-old boy beside him. His own permanent injuries meant re-learning the guitar, so he could fret with his right hand. Brain damage resulting from the injuries meant he had to ‘go picking for words like you’d pick fruit in an orchard’.

All of this is present in his song ‘Broken Fingers’. There is a certain heaviness in the emphasis and pronunciation, the words don’t come easily. You can tell they are sung by a man who has to hunt for words. Sam Baker was surrounded by a crew of supporting artists, friends willing him into making his music again. The album is his tribute. It invokes the memory of the boy and names Baker’s own loss. The lyrics are simple and eloquent:

These broken fingers

some things don’t heal

you can’t wake up from the dream

when you know the dream is real.

Sam Baker’s song takes hold of me. Suddenly I am weeping in the supermarket carpark. Some things don’t heal. There is a respectful knowing that doesn’t try to force healing or hope on people. I do the shopping slowly, with a new sense of gratitude.

In my childhood, I periodically heard preachers insisting on a kind of victorious Christianity. As if barracking for Jesus put you on the winning team where nothing could touch you. It felt like denial.

In the evening, I participate in the foot-washing ritual our church holds every Maundy Thursday. The night recalls the Last Supper when Jesus washed the feet of the disciples. Later that same night, in the Garden of Gethsemane, they abandoned him.

Prayers are spoken by candlelight in the darkened church. I am offered water for my feet, and fragrant oils, then towels to enfold them. I am offered wine to drink and bread to eat. In the quiet darkness I remember people who carry wounds that don’t heal.

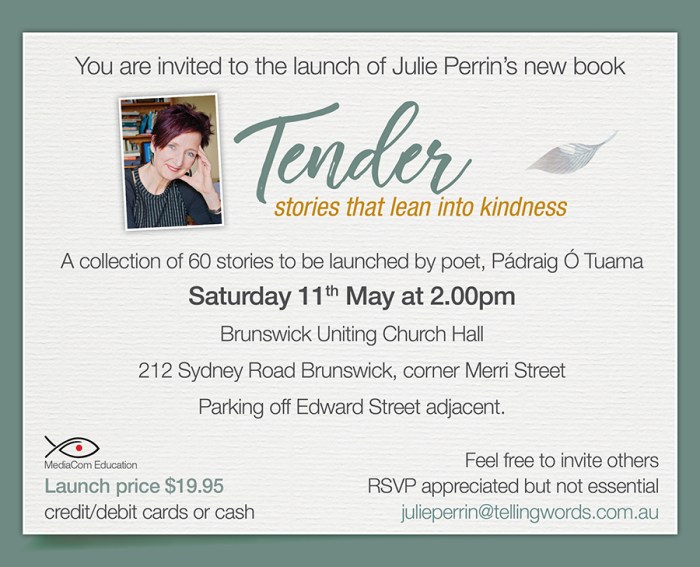

This story is one of 60 collected in Tender: Stories that Lean into Kindness, by Julie Perrin and forthcoming by MediaCom Education. Previously published in The Sunday Age faith column and Spinifex Blessing.

You are also invited to the book launch:

℘℘℘℘

JULIE PERRIN IS A MELBOURNE WRITER, ORAL STORYTELLER, AND ASSOCIATE TEACHER AT PILGRIM THEOLOGICAL COLLEGE, UNIVERSITY OF DIVINITY. SHE LIVES AND WORKS ON WURUNDJERI LAND.

Broken Vessel

broken body

broken heart

forever hanging

held by

the crying love of the Spirit

his wound

my hurt

our blood mixing together

his open arms

my nailed hands

pierced together

we share

the birth pain

we partake

the letting go

we release

the life to become

we form

the theology from the womb

we groan

with hope

we sob

with agony

until

creation is fully alive

until

lives flourish without blemish

℘℘℘℘