Acts of watching, and being watched, are deeply ambivalent phenomena. The English language has a range of more or less positive terms for these acts: vision, seeing/understanding, perception, discernment, as well as a host of imaginative, even fantasy conjunctions around seeing: imagining, envisioning, fantasising, displaying, spectacle. However, it has to be said that the negative or potentially malevolent terms for watching and being watched trip off the tongue more readily: voyeurism, spying, surveillance, scrutiny, leering, ogling, peering, staring, eye-balling, monitoring, inspection, bugging.

In relation to the age of so-called ‘capitalist surveillance’ (Zuboff, 2019), critic James Bridle defines this age in terms of human belittlement. More than ever, writes Bridle, subjects are captured and categorised by pervasive mechanisms of surveillance, producing a ‘litany of appropriated experiences … repeated so often and so extensively that we become numb, forgetting that this is not some dystopian imagining of the future, but the present’. Shoshana Zuboff, the author of the 2019 work The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power, which Bridle is reviewing, argues that around the year 2000 there was in many societies, globally, an exponential shift in modes of surveillance at both personal and social levels, through digitalisation. ‘Being watched’ takes on personal and transpersonal, ideological and more sinister overtones in Zuboff’s research into the netting of information by social media and governmental data collecting. Wikileaks is one, ongoing response to these phenomena, releasing as it has done over 10 million documents garnered by government and military media. In many ways the shift Zuboff describes might be better understood as an amplification of what prophetic novels such as George Orwell’s Animal Farm (1945) and Nineteen Eighty Four (1949), Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale (1985) and, differently, Cormac McCarthy’s The Road (2006) imagine. They are among many futuristic literary texts that evoke the suffocating and pervasive fear of being watched, hunted, categorised, known. The popularity of these dystopian texts is evidence of a widespread frisson, if not fear, amongst readers and film audiences, of the circumscribing of individual selfhood.

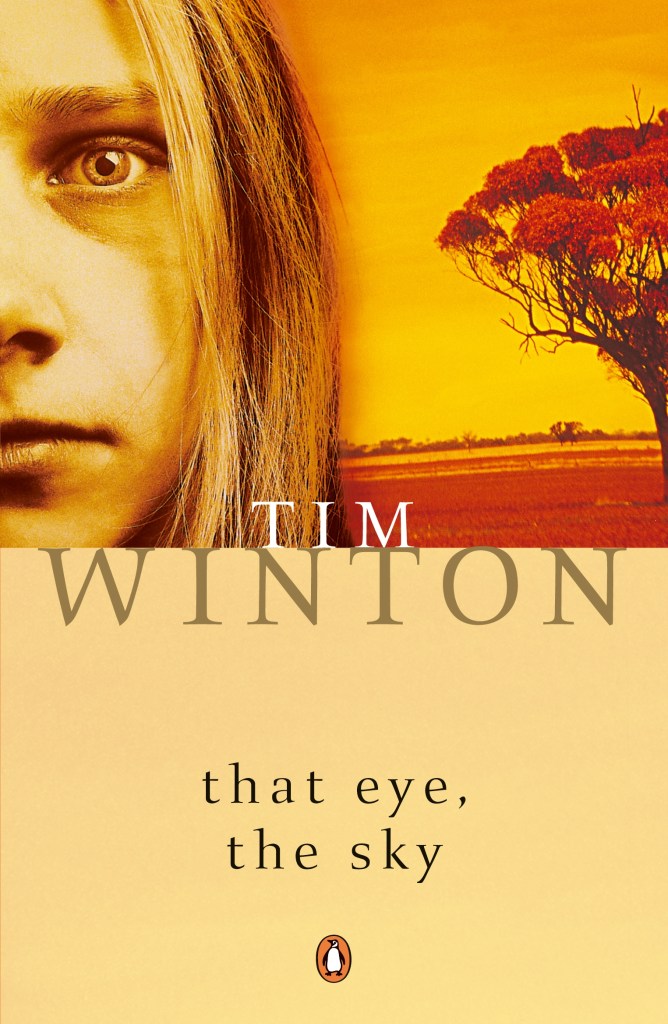

Zuboff’s research is prophetic, seeing into the consequences of present actions for a future hurtling towards us; and it enables me to take a fresh look (yes, the critic as watcher) into a 1986 Australian novel, That Eye the Sky, by well-known Australian author Tim Winton. Many of the texts named above probe threatened innocence and selfhood, as does Winton’s novel. However, That Eye the Sky is not dystopian. It is gentler, humorous, vernacular. Its brooding watcher – that eye the sky – takes the form of a glowing cloud hovering over the family house, and is mirrored in another watcher, a young, vulnerable boy entering early manhood, who sees things. Watching is part of the boy’s fertile and curious imagination, rather than being registered as malevolent. Theological, biblical, and mystical ideas about suffering, human love, trust, and hope flow through the novel’s vision of present and future, as the characters and their precarious forms of innocence are threatened by trauma, and by a wider urban world encroaching on their frugal existence. This is a remembered – mythical? – time before social media, set on the fringes of the urban, a time when children could go out and play alone, down by the creek, unsupervised.

Along with humour and the use of vernacular, That Eye the Sky creates its theology through a simplicity that underscores the darker, ongoing questions: is there an eye out there, watching? Is that eye benevolent, protective? Or neutral, deaf to human existence, or worse? The main character, twelve-year-old Ort Flack, asks these questions, as do readers, as the plot darkens.

Every ontological and social category in Winton’s That Eye the Sky is written under erasure, as already passing: childhood, hippiedom, Christianity, church, the bush, God, trust, knowledge, grief, love. As so often in the novels of Winton, the child, and a child’s eye-view, are central. Ort lives in a run-down house in the middle of the bush with his semi-hippy parents and sister. He is the narrator. He sees and feels things: clouds hovering over the house, red eyes peering in from the dark of the bush, a sky, benevolent or otherwise, looking down on him and his family, as trauma strikes. Ort is innocent, different, ostracised. He is sensuously alive to the smells and textures of the bush, to the sound of wind across the tops of the trees, observing the luminousness of moon and stars and the moods and feelings of his mother and sister as they grapple with the tragedy engulfing them. And he carries with him a constant sense of being watched over.

But Ort is also a voyeur. Turning thirteen, on the cusp of sexual awareness, and also alive to mystical possibilities, he peers through cracks and holes in the house’s walls, into bathrooms and bedrooms where he sees the desiring, lonely, threatened lives of his family: his mother, grief-struck and missing her husband Sam; his Dad, comatose, on the brink between life and death; his sister, Tegwyn, self-harming, promiscuous; Gramma, locked in dementia, and snoring; and Henry Warburton, the stranger who comes, in all his brokenness, to help, and to convert the family.

Outside the house – in the bush, down by the creek, with the chooks in the yard – Ort experiences a watching, brooding presence he cannot describe, but knows to be real. It is a force embodied in the cloud hovering above the house, in the stars and moon, in the beauty and ordinariness of the bush, in the strangeness of other people. It seems to be a presence neither malevolent nor benevolent, but Ort’s sensual experiences of it prepare him for the message from the stranger who comes to their door (Henry Warburton, injured preacher). Henry finally plucks up the courage to announce to the family that it is ‘God’ who hovers in everything, who watches over and cares for him and his family. Ort’s innocent openness allows him to receive the declarations Henry makes:

‘God told me to come to you’.

‘Who’s God?’

‘Ort, be quiet …’.

‘God is who made us and made the birds and the trees and everything. He keeps everything going, He sees all things. He is our father. He loves us’.

‘I thought it was just a word. Like heck. Is he someone? Mum?’

‘I never really thought about it, Ort … I, I …’.

‘So what did he send you here for?’ I ask Henry Warburton.

‘To love you’.

Tegwyn groans. ‘I thought you said you were alright’. [to Henry]

‘Did you get our names from God?’ I ask him. ‘How did you know our names? You knew all our names, and you knew about Dad’. (88)

The novel’s theology is alive with humour and with Ort’s openness, if not naivety. Mother and son are persuaded by the stranger to give ‘God’ a go, although teenage Tegwyn is a harder nut, sceptical, infused with sexual more than metaphysical needs. Ort is particularly intrigued with the promise of being known, named, understood. This openness rings true psychologically, for Ort is a vulnerable twelve year old who is being confronted with the possible death of his father, a figure who has been completely benign and loving in his son’s life. Alice, his mother, is equally child-like in many ways, loving, trusting, unused to asking metaphysical questions: ‘I never really thought about it, Ort’. This is, clearly, a world before Google, before social media, where information, authority and knowledge have different parameters.

And so, the household receives another pair of eyes, another watcher, into its midst – Henry and his message – through need and trauma. Winton is rarely judgemental of the watchers and their objects of desire. All are whirled in a dance of fear and longing, a need for certainty when none is available. Alice and Ort find some comfort in the evangelist’s definitive theology and practical compassion, clutching for reassurance. Their baptism, acceptance of daily bible readings and communion lead to the wonderful (horrifying!), parodic account of the fundamentalist church just down the road, towards the end of the book. The haplessness of Alice and Ort’s one-time visit to the church at the back of the Watkins’ drapery store is superbly rendered, as Winton satirises a self-righteous, fear-mongering brand of 1960s Christianity. The church service is full of rigidity and surveillance: the mark of the beast, the wrath of God, plagues upon men; a place where ‘everyone in the room is looking at us’, and where the preacher declares in a booming voice: ‘Read the signs! Read-the-signs! The Antichrist himself comes … The-need-is-great! Pressing. Urgent. How will we stand in the tribulation?’. Winton creates the jerky stresses and freighted vocabulary of the preacher who condemns the heathen world, a world against which salvation is available for a narrow band of believers. But it is the innocence and intuitiveness of Alice that wins the day. Refusing to succumb to the judging eyes and exclusions of the congregation, she jumps up to leave, pulling Ort with her. Alice declares, in the full force of her outraged innocence:

‘You don’t have to shout. We’re not animals, you know. And not even God’s animals should be shouted at like they’re made of mud’. (126)

Simmering in the background of the narrative, across these events, is the presence of the father, Sam, comatose, hovering between life and death, watched over by Alice, Ort, Tegwyn and Henry Warburton. There is never any doubt that all the family, and the stranger, unconditionally love and watch over Sam who seems to see nothing, staring vacantly as they feed, bathe and talk to Sam, taking him for walks in the wheelchair.

The novel draws rapidly to a climax. Against all this festival of watching and being watched, the characters and the readers are drawn inexorably to a scene, narrated by Ort, that resolves nothing, finally, but that points towards new possibilities:

Everywhere, in through all my looking places and all the places I never even thought of – under the doors, up through the boards – that beautiful cloud creeps in. This house is filling with light and crazy music and suddenly I know what’s going to happen and it’s like the whole flaming world’s suddenly making sense … [I] burst into Mum’s room and there’s my Dad with these tears coming down his cheeks, pinpoints of light that hurt me eyes … His eyes are open and they’re on me and smiling as I come in shouting ‘God! God! God!’ His face is shining. I’m shaking all over. ‘God! God! God!’ (150)

Ort’s eyes are opened – ‘the whole flaming world … suddenly making sense’. His father’s eyes are open, and expressive for the first time. And ‘that beautiful cloud’ has moved from symbolic, ambivalent presence to a sensuous, infiltrating, clarifying atmosphere, bringing father and son to a crucial moment of … resurrection? Renewal? Clear-sightedness?

The reader is left in a place that is not certainty, but something is coming to a climax. Ort’s innocent expectations are turning to action, and images of eyes, seeing, tears, ‘pinpoints of light’ predominate in the final scene. Ort says his father’s eyes are ‘on me and smiling’, and miracle, or at least a change, is happening. Certainly Ort – full of hope and love – is expecting miracle.

So what does That Eye the Sky offer readers, when we reflect on the phenomena of watching and being watched? God had been unknown to Ort – ‘I thought it was just a word. Like heck. Is he someone? Mum?’ But the child entering into early manhood has also long intuited, in the natural world and in his family relations, a presence that ‘keeps everything going … [who] sees all things’. As the child literally takes to heart the biblical injunction to anoint with oil and pray for the ill, he grabs the safflower oil and the big black family bible, believing, hoping, seeing what he so desperately needs to see, his father, eyes open and smiling at him; light and music filling this house of trauma; the whole world suddenly making sense. For this climactic moment, and possibly into the unwritten future, that watching eye is powerful, intervening and benevolent.

[Reposted, with edits, from Ethos.]

℘℘℘℘

Lyn McCredden is Professor of Australian Literary Studies at Deakin University, Australia. She is the author of Intimate Horizons: the Post-colonial Sacred in Australian Literature (with Bill Ashcroft and Frances Devlin-Glass, 2009), Luminous Moments: the Contemporary Sacred (2010), The Fiction of Tim Winton: Earthed and Sacred (2017), and a poetry collection, Wanting Only (2018). She LIVES AND PLAYS ON WURUNDJERI LAND.