Icon Exhibition

Paul Mitchell’s new book of poetry, High Spirits (Puncher and Wattmann, 2024), will be launched in the Westgate Baptist Community Hall (16 High Street, Yarraville, Victoria) on Saturday 25 May. Michael McGirr, author of the best selling non-fiction work, Books That Saved My Life, will do the launching. 3pm for a 3.30pm start. All welcome.

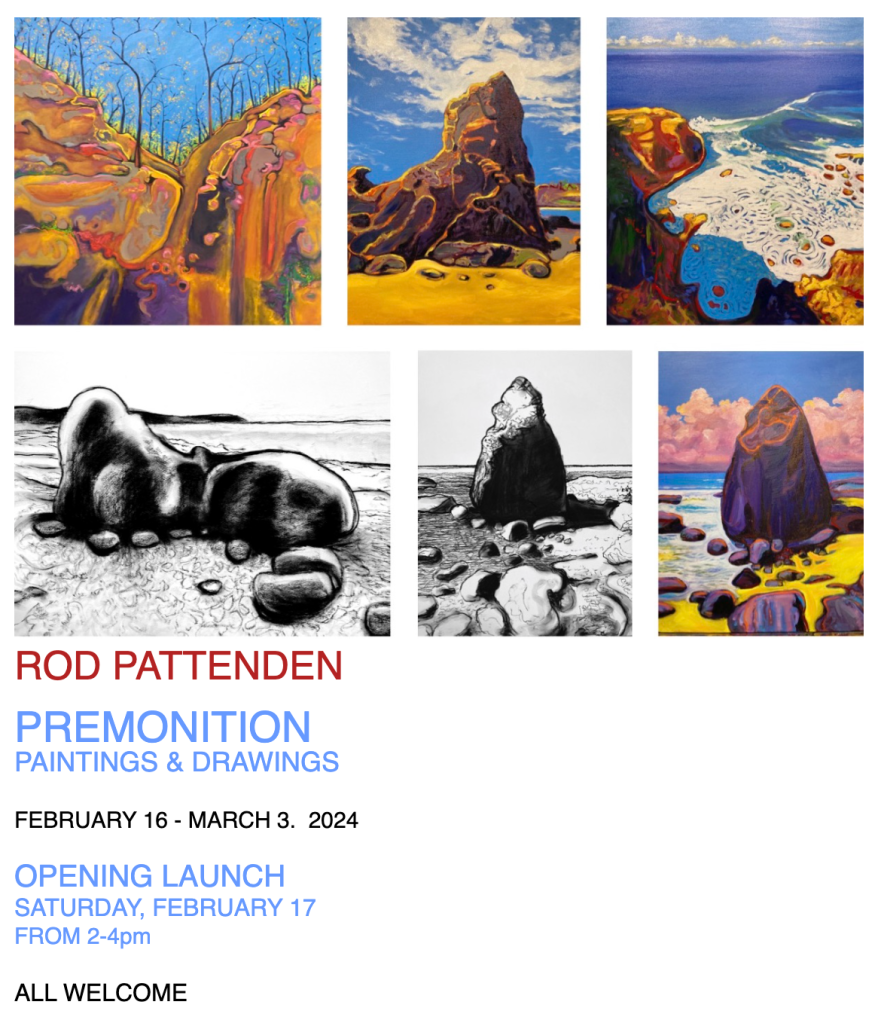

Join us for the Opening Launch of Premonition, by Rod Pattenden on Saturday 17 February, from 2 pm.

This is Rod Pattenden’s second solo exhibition at ASW and promises to be another celebration of sensuous colour and form. Pattenden describes this new body of work as:

New paintings and drawings with a vivid presence and an uncertain future breaking in. Works in vibrant colour, small to large scale with a range of stark large scale charcoal drawings.

The Centre for Theology and Public Issues at the University of Otago has extended an invitation to an open lecture by Professor Ephraim Radner.

The lecture will be on ‘Art and the Christian in an Age of Mass Culture: A Theological discussion on a famous argument of Walter Benjamin regarding art and its reproduction’.

Time: Tuesday 13 February at 5:15pm – 6.30pm (NZ time)

Place: Archway 2, University of Otago, Dunedin, or livestreamed here.

Rod Pattenden, Jason Goroncy, and Maissa Alameddine were recently interviewed by Meredith Lake for the ABC’s Soul Search program. We talked about art, theology, and other stuff, and about how art really matters in sustaining and developing what is most eloquent and wonderful about being human.

You can listen to the interview here.

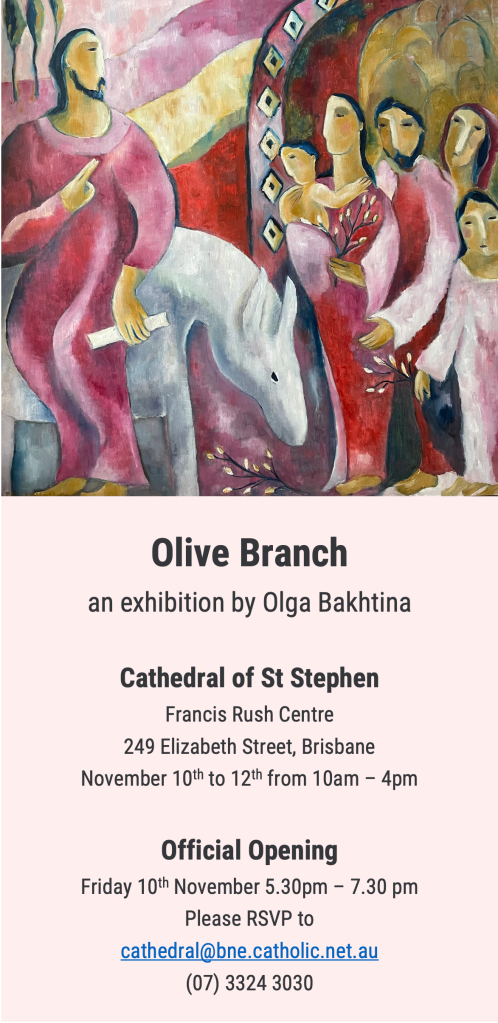

Olga Bakhtina is a Queensland-based artist working in oil and charcoal. She studied painting 15 years ago in the Sultanate of Oman while living there with her family for 4 years. Currently, she studies the history of art at the University of Queensland. Olga has a passion for Early Renaissance art, in which she finds serenity and inspiration.

Since her first solo exhibition in 2012 in Oman, Olga has been exhibiting regularly across Australia. Her recent solo exhibition, ‘Good Samaritan and other Biblical Stories’, showed in St John’s Anglican Cathedral, Brisbane, in July 2023. Olga has been the finalist and winner of a number of Australian Art awards, including the COSSAG (Cathedral of Saint Stephen Art Group) Award in 2016 and 2018.

Olga’s artworks are in the collections of the Archdiocese of Brisbane, the Australian Catholic University, Rosebank College, and St Anselm Abbey, New Hampshire, USA. Her work also hangs in various private international collections.

Olga’s work has been published in various publications worldwide, most recently in The Double: Identity and Difference in Art since 1900 (National Gallery of Art, 2022).

In 2022, the Archdiocese of Brisbane created a video series titled Art Aficionados, in which Olga’s Good Samaritan painting featured:

Olga writes:

I’m often asked why I paint Bible scenes. There are several reasons, but the most important one is that my paintings are not just about the Bible. They are about humanity and what comes with it – the beautiful things in life, like love, unexpected kindness, devotion, and sacrifice. But humanity also brings pain and tragedy – betrayal, greed, cruelty, and war. Has anything really changed since the Bible was written?

Nowadays it seems that the world is collapsing back to biblical times, as if there is a crack in civilisation. On one hand, there is humanism and advanced technologies, which Joshua, who stopped the sun in the Old Testament, did not dream of. On the other hand, there remains a lot of hate and barbarism, which sadly we continue to see around the world way too frequently. Sometimes, it feels like we’re flipping through the Bible and checking it with our reality.

I think we can all relate to the biblical stories and lessons, in one way or another. The Bible has lots of answers. My biblical paintings are my attempts to find them, to process what is happening in the world, and in my own life. They are my prayers, too. Someone said that art is the highest form of hope.

Olga is having an exhibition as a part of the 150th Anniversary celebration programme of the Cathedral of St Stephen, in Brisbane. The exhibition opens this Friday evening. RSVP to cathedral@bne.catholic.net.au or (07) 3324 3030.

℘℘℘℘

Alive

if you still your heart

to hear the tales of ocean waves

if you lay your ear on a seashell

to learn the dance on a distant shore

if you open your eyes

and pay attention

to tiny stamens

with awe

if you sensitize your nose and echo

moods of rainforests

with reverence

if you breathe in deeply

and caress gumtrees

with gratitude

if you lengthen your antennae

and receive outpourings of

divine love and beauty

every part of you

awakened

attuned

alive

生机

如果你安静你的心

聆听海浪的故事

如果你把耳朵贴近在贝壳上

在遥远的海岸学习舞蹈

如果你睁开眼睛

并留意风中

那轻微抖动微小的花蕊

抱着敬畏之心

如果你让鼻子灵锐

和雨林的情态

相呼应

怀着崇敬之肠

如果你深深地呼吸

抚爱星辉包裹的胶树

带着感激之情

如果你延长触角

并领受神圣的爱与美

倾盆降下

你的每一部分

觉醒

谐和

生机

℘ ℘ ℘ ℘ ℘

A Sacred Space

weep and lament

loudly or quietly

but certainly

as much as you can

in the parched and weary land

a wilderness

a wasteland

where hope is no more

……

cracks start to open

tears spring up

from within

calling all

to sit and share

openly and honestly

letting fountains surge

from underneath desert land

……

a rainforest of greens

emerging

moisturizing

replenishing

enticing you

to play and dance

in rhythms and shades

of sunlit sprinklings

一个神圣的空间

哭泣和哀叹

高声喊叫或轻言细语

但肯定得

痛痛快快地

在干旱疲惫之地

一片旷野

一片荒地

希望已不复存在

……

裂缝开始张开

泪水源自内心

而涌出

呼唤所有人

开诚布公地

坐下来分享

让喷泉从沙漠的底层涌出

……

一片翠绿的雨林

冒出地面

滋润

补充

引诱你

在阳光洒落的节奏和色调中

尽情玩耍和舞蹈

Jason Goroncy and Rod Pattenden are delighted and honoured that their edited book, Imagination in an Age of Crisis: Soundings from the Arts and Theology, has been shortlisted for the 2023 Australian Christian Book of the Year Award. One of ten shortlisted volumes chosen from over 100 published works, this recognition attests to the importance of this innovative collection of essays and reflections by artists, poets, and academics.

The book brings together a creative conversation about the role of the imagination through the work of creatives and academics as they reflect on the many ways in which the arts and theology provide resources for negotiating change and generating hope during a time of rapid cultural change and an uncertain future. It includes significant Australian perspectives that are set within a wide international context and conversation.

The book has received widespread recognition by a number of reviewers. For example, Angela McCarthy, Adjunct Senior Lecturer at the University of Notre Dame, writes:

This collection of writings ranges in depth and focus to bring a richness of cultural awareness and imaginative power that indeed brings hope and value to our culture through the interactions and power of artists.

And Catherine Lambert describes the book as:

A montage of evocative poetry, poignant artworks, insightful essays and personal reflections. Each piece is an invitation to look more deeply, linger a little longer and savour each offering. This is not a book to devour, but invites a more reflective contemplative reading. … Through the generous sharing of the contributors, the reader is invited to engage both their head and their heart in responding to this age of crisis. … [A]n invaluable gift to the conversation between arts and theology.

This year’s Australian Christian Book of the Year will be announced in a ceremony in Melbourne on 31 August.

A video introduction and review of the book, plus details on how to obtain a 40% discount via the publisher’s website, is available here. Copies of the book are also available from wherever decent books are sold.

Beginning in 2017, Ridley College’s biennial Evangelical Women in Academia conference is a women-only event seeking to platform, promote, encourage, train, equip, and inspire Christian women in academic work across Australia. This year’s conference keynotes are given by constructive theologian Dr Natalie Carnes (Baylor University) teaching on ethics, art, and poverty in Christian theology.

Friday’s event will feature Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander artist and educator Safina Stewart speaking about art, faith, and indigenous spirituality. Safina will also lead in some hands-on responsive creative work of the participants’ own.

In addition, short papers and workshops/seminars provide an opportunity to learn from a wonderful lineup of Australian Christian women HDR students, academics, writers, and practitioners.

To find out more, visit here.

On 15 June, from 7.00–8.15 pm (New Zealand time), the theology programme at the University of Otago is hosting a public seminar with Dr Christopher Longhurst on the subject of Renaissance art. Details and Zoom link below: