As both an artist and a pastor, I am well aware of the capacity for works of art to bring healing, to provide a container for grief and loss, and to create a future based in hope. I have also experienced the capacity for works of the imagination to break down the supposed barriers between the church and its community, between the holy and the profane, the sacred and secular, and to create a fruitful conversation about life’s meaning. I have great hopes that the arts provide us with resources for engaging the culture we inhabit and for dealing with any of the big difficult issues we face together. But despite these hopes, I am really struggling with how to respond at a visual level to the aftermath of the Royal Commission into Child Sexual Abuse, and the terrible stories that have surfaced into public consciousness. As an artist, I wonder how to help people visualise the trauma and pain of such experiences, and how the Church as an institution allows for this to be made present in sign, symbol, and art making. How might art help the healing process and bring reconciliation and understanding?

It was about fifteen years ago through my work with the Blake Prize that I first began to observe visual responses to this issue. In 2008, Rodney Pople submitted a work entitled Last Supper, a work that proved to be something of a premonition of the impending crisis for organised religious institutions. A reference to the Last Supper of Jesus with his disciples has been pushed to the back of the picture as something of incidental interest. What takes centre stage is a vast chandelier that seems to shudder under its own weight of self importance. Not a light but a weighted piece of staging that is about to come crashing down. The metaphor is clearly about a structure that has become too focused on its own importance and grandeur, so much so that even the Last Supper has been pushed to the periphery. Rodney Pople went on to deal more directly with these issues. In one of his later exhibitions, held in trendy Paddington in Sydney, a group of pious folk camped outside praying for his soul and for those brave enough to enter the gallery under prayerful siege.

But Pople was correct in anticipating that there would be a shaking of foundations and a rattling of fences. It was during 2015 when the Royal Commission heard stories in the city of Ballarat that ribbons began appearing on the fence of St Patrick’s Roman Catholic Cathedral. They were tied on the fence as a simple memorial to those who had died or still suffer as a result of a history of abuse. This simple act of remembrance has spread quickly around Australia and is now found all around the world. This gesture has, however, not always been well received by those on the inside. Whether it was Church authorities or parishioners there were reports of ribbons being removed. The visibility of the act of colourful ribbons fluttering in the breeze was perceived by some as a protest of anger at the Church or at least a criticism of its silence and lack of visible response. St Patrick’s Cathedral has continued to dialogue with this wider ribbon community and there are now plans for the fence to open up into a memorial garden where a more permanent space of recognition is be created. Through the visual form of ribbons, known locally as the ‘Loud Fence’, boundaries have been shifted and a new more open conversation has begun.

In Geelong, at St Mary’s Basilica, the Loud Fence response took a different turn. One of the key priests on staff actively worked with survivors through the Life Boat Project and with the assistance of a group from a Men’s Shed found a means of preserving the ribbons and the heartfelt gestures that had created them. A container in the form of a boat has been introduced inside the Basilica where ribbons can be permanently stored after they have flown on the fence. This shifts the visual reception of the ribbons to a more permanent memorial where they are being treated with dignity and respect. This boat has become part of the interior fabric of the Church alongside other memorials that remember significant moments of national and local history. What is being preserved is not just silk threads, but the deeply-felt gestures that have been repeated over and over again as people express their sense of grief and loss. Gathering them up for preservation emphasises the importance of these small acts of grief and remembrance. Someone is listening, noticing, seeing. The Loud Fence project looks for a community of people who speak up and act on behalf of those who are victims.

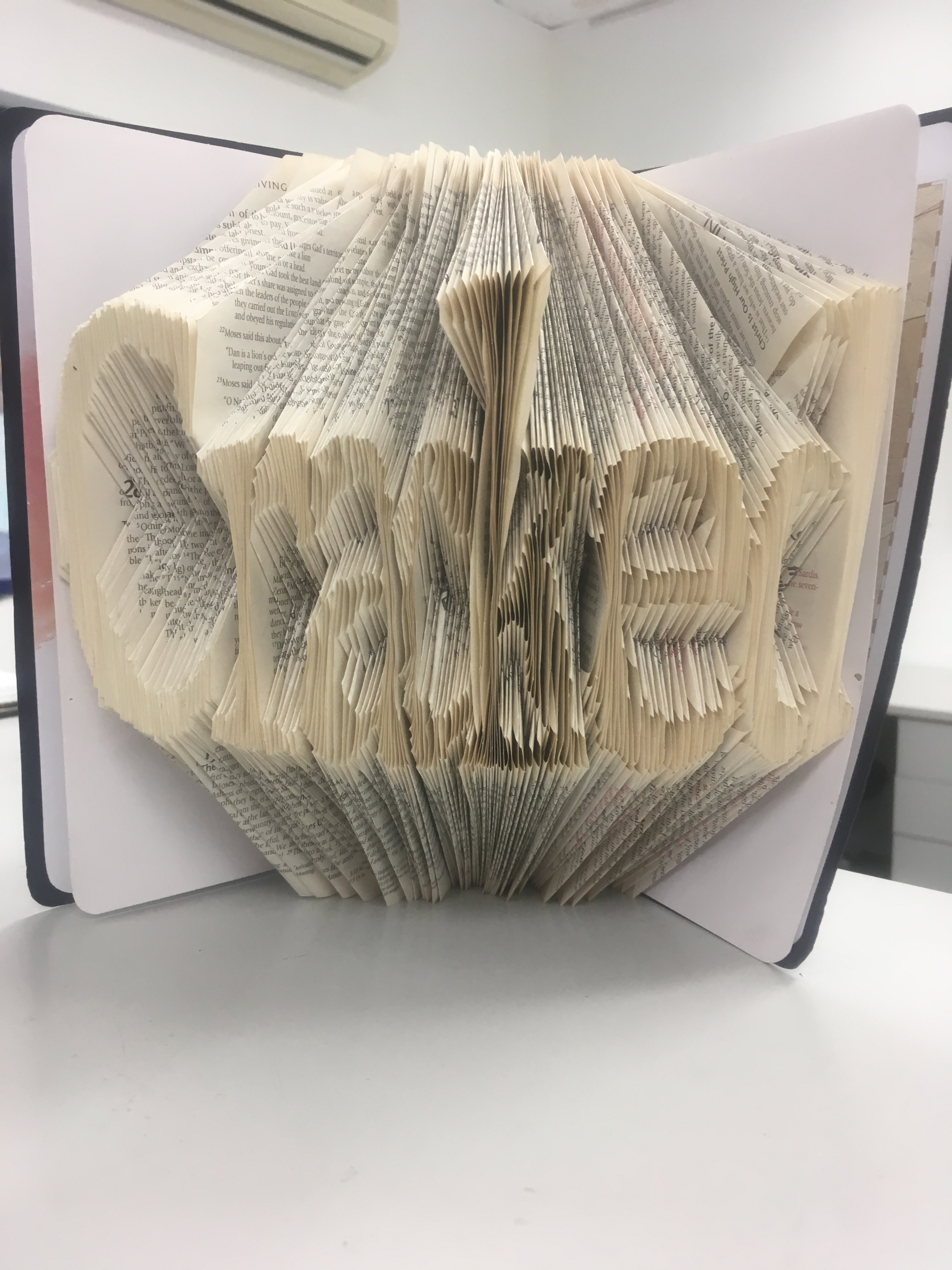

In my local city of Newcastle, like in many cities around Australia, ribbons appear and disappear off the fence of the local Cathedral. It is a disputed space between those who want this to be visible and those who wish it to remain hidden or at least managed out of sight. This is a pressing issue as in my city the extensive volume of abuse and the individual number of stories is staggering. Thousands of people in my local community are suffering the long-term effects of grief and trauma, including their families, neighbours, as well as the educational and religious institutions of the region. It must be one of the largest contributors to mental illness and social trauma in my local community and it is otherwise hidden. But it is also appearing more often in the work of local artists, like in the work Cracked by Janita Ayton. Here, the soft pages of a Bible have been repetitively folded over to spell out the word cracked. This is only observed when the Bible is opened and the word then literally spills out. Clearly, the culture of secrecy and power that once clothed the Church has now been cracked. For the first time in Australian history, the Church has been drawn to public account for its actions, inactions or shameful cover-up. This assumed privilege due to social power or religious authority has been found wanting. The Church is not above the law; it is accountable to the people it seeks to serve.

Cracked is an artwork that visualises the crisis of authority facing organised religion. But it also offers, to my mind, a way forward. When something is cracked, then what is contained inside can get out. Rather than fear being the first response, a response that reinforces denial and secrets, here is an invitation to find within the life of the Church a range of other responses that focuses on victims and those impacted by this history of abuse. The Church has nothing to fear in losing its well-preserved social power if it, in turn, recovers what is at its heart in terms of compassion, forgiveness, and love. Self-preservation cannot be the default position of the Church when facing this sort of accountability in the public square. Here is an opportunity to visualise compassion and a form of agency based on love. The loss to the Church in the face of this ongoing scandal is incalculable, but the opportunity for the Church to renew its purpose will be life-giving and renewing. Cracked leaves me with the possibility of such a hope.

Rod Pattenden is an artist, art historian, and theologian interested in the power of images. He lives and works on Awabakal land.