Icon Exhibition

There’s a timely reflection by Seung Heon Sheen over at Transpositions on the relationship between AI-generated art and iconography, with implications for how we might consider the relationship between an artist and their work more generally. It draws on relevant texts from the iconoclast controversies of the eighth and ninth centuries. Here’s a snippet of the argument in nuce:

… any ‘icon’ generated by a ML algorithm would be inherently idolatrous since the relationship between the image and the archetype would be severed. That is, although the works produced by a human iconographer and an AI ‘iconographer’ may be outwardly similar, inwardly they would be radically different due to the disparity in the process of their creation. A human iconographer faithfully contemplates and depicts the archetype; an AI abandons the archetype and merely replicates its images. And if this is so in the case of iconography, it implies a danger of idolatry in involving AI in religious art or employing it for religious purposes.

You can read the full piece here.

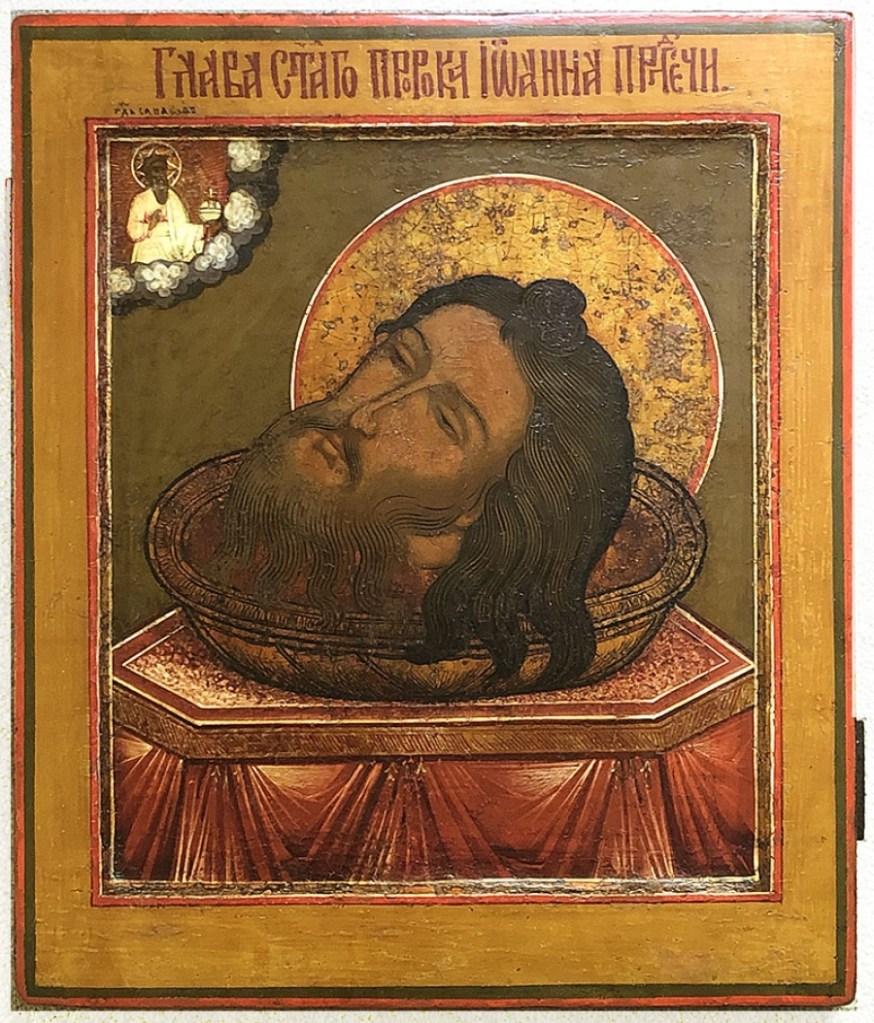

Danylo Movchan is a Ukrainian artist who lives and works in Lviv. Below is a photo of an icon written by Movchan, his response to Russia’s bombing yesterday of a Ukrainian children’s hospital and maternity ward, in the city of Mariupol.

Господи помилуй.

I first met Michael Galovic through an icon painting workshop in the mid-1990s. His religious art not only covers a vast range of icons that draw upon his deep understanding and respect for the form from its earliest origins through to the present day but also covers contemporary work.

Michael’s most recent project has been a very challenging and self-imposed task. Its focus has been primarily on the representation of ‘the Celestial Ranks’, predominantly as shown in Orthodox art, but also with examples from late medieval, early Renaissance, and Islamic art. Each of the many wonderful images expresses what would seem almost inexpressible: non-corporeal beings made manifest. The exhibition based on this work, and which is currently on display between 9–19 March at the Australian Centre for Christianity and Culture, Canberra, also highlights both the meaning and the beauty of the variety of portrayals, whether it be in terms of the images’ backgrounds or in such elements as the stunning array of angels’ wings. The icons in the exhibition illustrate a journey that is both geographical and through time.

My focus here, however, will be predominantly on his representation of two of the most significant and defining events in Christianity – the Annunciation and the Resurrection – as portrayed in the icon of ‘The Myrrh-bearing Women’, as well as the concept of the Trinity. Each image deepens one’s understanding of the religious art of the past and present, as well of a sense of tradition, while also expressing the perception and perspective of its creator:

Each mortal thing does one thing and the same:

Deals out that being indoors each one dwells;

Selves – goes itself; myself it speaks and spells

Crying Whát I dó is me: for that I came.[1]

In terms of the Orthodox tradition, icons are perceived, Annemarie Weyl Carr observed, as participating in the divine:

As angels and saints are images of God, icons, in turn, are images of them and so participate in the emanation of their sanctity. The crucial synapse between divinity and created matter was bridged by the incarnation.[2]

The richness and variety of the icons is expressed through new iterations that nonetheless remain firmly grounded within the Orthodox tradition. The icons of the past were not mechanical copies of previous work. The tradition evolved not through meticulous repetition but through observing and understanding the symbolism and underpinning theology inherent in the creation of the icon. Each is also influenced by the time, background, and perception of the person making it.

To appreciate the beauty and theology of an icon is ultimately to be able to appreciate the immanence of God in creation:

He fathers-forth whose beauty is past change: Praise Him.[3]

The Icons of the Annunciation

Michael noted that his ‘Royal Doors’, an image of the Annunciation, is a work that has been 47 years in the making. This gives some sense of the process: it takes enormous patience in feeling one’s way into the image, as well as an understanding of the level of experience and technical skill needed to do such a work justice. It is a testament to Michael’s commitment to creating an image that brings alive the moment of the Incarnation in all its vividness and freshness. There is a wonderful balance between the sense of movement in the depiction of Gabriel, conveyed by both the pose and dynamism of the contrasting highlights, and the Theotokos’ acceptance, shown in her gently-bowed head and hand gesture.

It is difficult just to convey a sense of the intricacies of the craftsmanship required in the creation of this wonderful depiction of the Archangel Gabriel and the Theotokos. It began with the painstaking application of multiple layers of gesso to the intricately-carved wooden surface and then the gilding of the entire piece. This was followed by the meticulous translation of the drawn images onto the surface, with some parts being carefully embossed or stippled, as can be seen in the exquisite halos.

The actual painting of the image with egg tempera was a further level of challenge, with each layer needing to be completely dry before the next layer was attempted – often a matter of days, rather than hours.

The impermeability of the gold also makes it an exceptionally challenging surface on which to paint. The difficulty of the challenge is underscored by Eva Haustein-Bartsch’s comment, in her description of the Royal Door in the Recklinghausen Ikonen-Museum, that ‘what is completely unusual and probably unique about this door are the images painted on it over a gold background’.[4]

Michael has created a truly outstanding depiction of the imagery frequently used on ‘Royal Doors’, bringing together many theological and technical aspects of iconography to delineate the entry to the sanctuary, considered in Orthodox theology to be ‘Heaven placed on earth’, as it contains the consecrated Eucharist, the manifestation of the New Covenant.

The second Annunciation, in a more contextualised setting, also captures the moment of the Archangel Gabriel’s first addressing Mary. There is the same sense of movement as in the ‘Royal Doors’ in the placement of the feet, with the role of messenger indicated both by the rod

being carried and the hand gesture indicating speech. Mary’s gesture here is one of enquiry – ‘“How will this be”, Mary asked the angel, “since I am a virgin?”’ (Lk 1.34)

This icon again highlights that Michael’s work, while maintaining the theology and often the form of earlier icons, by no means consists of making a mechanical copy of an earlier image! The vivid light blues on a deeper blue background sweep through from the tips of Gabriel’s wings to the sleeve of his under-gown with the same tones used in a static mode in the pillar beside Mary. This contrast is repeated in the lower part of the icon, with the rippling effect of Gabriel’s hem counterpointing the ‘stillness’ of Mary’s undergarment.

Another beautiful detail is the way in which the beam of light, with its image of the dove representing the Holy Spirit, is transparently overlaid on the red cloth. Each detail is indeed meticulously placed and adds to the viewer’s understanding and reception of the image, with the draped red cloth indicating that the scene is taking place in an interior. The colour flows through to Mary’s cushion, the thread she is holding and her ‘royal’ footwear. This image again emphasises the way in which the same image (that of the Annunciation) can both take inspiration from the past and create a new and vivid image. This is what keeps the tradition alive and relevant.

The inspiration for the third Annunciation in the series came from a faded and almost unreadable copy of an Annunciation from sixteenth-century Russia, and which had deteriorated to the point that, while the basic structures could be made out, that was about all. Michael always enjoys a challenge.

The image is also a very unusual one in that it shows darkened apertures in both the buildings and the holes in the ground, especially the fissure appearing between Mary and the Archangel. This could conceivably be highlighting the significance of Christ’s incarnation through referencing those icons of the Crucifixion where there is a dark aperture beneath the cross, into which Christ’s blood flows, signifying the redemptive nature of his death. The Crucifixion is inherent in the Annunciation.

The dark spaces dramatically highlight the wonderful luminosity that Michael has achieved in the depiction of both Gabriel and Mary. It, possibly more than any other icon in the exhibition, illustrates the concept of feeling one’s way into the image. It required a deep understanding, much thought and subsequently a painstakingly slow application of layer upon layer of semi-transparent egg and pigment washes to create the tonality that brings the image to life.

The fourth Annunciation is based on a fresco with a suitably-Aegean blue providing a background against which the figures and architecture stand out vibrantly, capturing the moment of the Incarnation.

These four images exemplify both the richness and diversity of traditions over at least four centuries and the value of bringing them alive in varied and beautiful iterations in the twenty-first century. While each highlights the role of the Archangel as the servant and messenger of God, as identified by the armband, and captures the contrast between movement and stasis, the nuances in the portrayal of Gabriel and Mary and the treatment of the backgrounds, ranging from the ‘uncreated light’ of the ‘Royal Doors’ to the texture and abstraction demonstrated in the three following images, exemplify the beauty, scope, and continuing significance of Iconography.

At the still point of the turning world. Neither flesh nor fleshless;

Neither from nor towards; at the still point, there the dance is …[5]

From the Annunciation to the Resurrection

Gabriel’s role as messenger is also highlighted in the icon of ‘The Myrrh-Bearing Women by the Tomb’, a diaphanously-rendered image of the women visiting Christ’s tomb. The delicacy and aptness of the detail, such as the fruitfulness of the trees, illustrates the richness in the variety of the use of imagery in the context of the Resurrection.

‘Angelic Exuberance’ is another vivid expression of the Resurrection – a dynamic and powerful iteration of a golden Archangel Gabriel that captures the light and joy of the event in a contemporary image that also evokes a continuing tradition: that of the White Angel, which is a detail of one of the best-known frescoes in Serbian culture, situated in the Mileševa Monastery.

‘The Assembly of Angels’ also includes the Archangel Raphael, whose name means ‘God has healed’. In conjunction with the image of Christ it highlights, for me, the nature of redemption through the Incarnation. The Christ Child is framed by an intricate rainbow-like aureole or medallion. The golden brightness in the central band of the medallion gives a wonderful vividness and focus to the work. This icon, in conjunction with its vibrancy highlighted through the angels’ garments and royal footwear, nonetheless seems to be set beyond time with a neutral background that portrays the figures as if floating in space. This feeling of weightlessness is enhanced by the folded position of the wings.

It seems fitting that the final image considered should be that of ‘The Holy Trinity’, which radiates calmness and certainty, as well as embodying a significant aspect of the development of portrayals of the Trinity. The process of the ‘three angels’ form for representing the Trinity began with icons of the hospitality of Abraham, which illustrated the visit of the three angels, in human guise, to Abraham.

This is a beautiful and elegant composition, based on a work by arguably the best Serbian iconographer – Zograf Longin. It is an icon that expresses the tripartite nature of God as expressed in the New Testament while highlighting the continued relevance and significance of the Old. Michael has dedicated a year to the completion of this project – one that needed fifty years practice and deepening of understanding for its making. He has brought alive the beauty and theology of differing traditions and forms in a way that is truly breathtaking.

℘℘℘℘

[1] Gerald Manley Hopkins, ‘As Kingfishers Catch Fire’.

[2] Annemarie Weyl Carr, ‘How Icons Look’, in Imprinting the Divine: Byzantine and Russian Icons from the Menil Collection (Houston: Menil Collection, 2011), 23.

[3] Gerald Manley Hopkins, ‘Pied Beauty’.

[4] Eva Haustein-Bartsch, Icons (Hong Kong: Taschen, 2008), 62.

[5] T. S. Eliot, ‘Burnt Norton’.

What kind of time is this? And what might such a time mean for artists and their work?

Beyond the very real financial hit that many artists are currently taking, a great many of us, artists included, are welcoming this abnormal moment to ask other questions – existential questions, and questions about our regular habits and commitments, for example. It is suggested that to try to carry on with business as usual, however tempting and well-intentioned that might be, would be to forego a rare opportunity to reimagine and re-embody other modes of our living. Others are turning to all kinds of creative endeavours. Others still – including artists – are asking whether now is really the time to make art at all?

Of course, we’ve been here before. This is hardly the first time in our history that such questions have been asked.

In the aftermath of WWII, where the dominating backdrop was clearly otherwise than it is today, the philosopher Theodor Adorno, in his Negative Dialectics, raised the question of whether the traumas of Auschwitz mean that ‘we cannot say anymore than the immutable is truth, and that the mobile, transitory is appearance’. It is not, he insisted, a case of an impossibility of distinguishing between eternal truth and temporary appearances (Plato and Hegel had already showed us how that could be done); it’s just that one cannot do so post-Auschwitz without making a sheer mockery of the fact:

After Auschwitz, our feelings resist any claim of the positivity of existence as sanctimonious, as wronging the victims: they balk at squeezing any kind of sense, however bleached, out of the victims’ fate. And these feelings do have an objective side after events that make a mockery of the construction of immanence as endowed with a meaning radiated by an affirmatively posited transcendence.

Put more plainly, our emotional responses to horrors of such magnitude ought to outweigh all our attempts to explain them. It was this conviction too that led Adorno to state famously (in his essay ‘Art, Culture and Society’) that ‘to write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric’, and that ‘the task of art today is to bring chaos into order’. The line between explanation and intelligibility has been severed. In the wake of such, we are left with the possibility of Adorno’s ‘negative theodicy’, a kind of theodicy in which the old intellectual and philosophical distance is impossible. If we are to make any headway at all in recognizing how the Nazi death camps succeeded in the destruction of biographical life, and reorientate our thinking in response, Adorno argues, we must learn how to regard Auschwitz as the culmination of a trajectory embedded in the history of western culture in the wake of the Enlightenment. In other words, there can be no genuine acknowledgement of the Holocaust that does not begin with the realization that ‘we did it’.

Today, our questions may be otherwise. For some of us – for those, for example, trying to discern (or create) lines between unbridled capitalism, ecological disaster, and global pandemics – perhaps they are not so.

In his latest post for The Red Hand Files, musician Nick Cave responds to a series of questions about his own plans for this time during the corona pandemic. His reflection is worth repeating here in full:

Dear Alice, Henry and Saskia,

My response to a crisis has always been to create. This impulse has saved me many times – when things got bad I’d plan a tour, or write a book, or make a record – I’d hide myself in work, and try to stay one step ahead of whatever it was that was pursuing me. So, when it became clear that The Bad Seeds would have to postpone the European tour and that I would have, at the very least, three months of sudden spare time, my mind jumped into overdrive with ideas of how to fill that space. On a video call with my team we threw ideas around – stream a solo performance from my home, write an isolation album, write an online corona diary, write an apocalyptic film script, create a pandemic playlist on Spotify, start an online reading club, answer Red Hand Files questions live online, stream a songwriting tutorial, or a cooking programme, etc. – all with the aim to keep my creative momentum going, and to give my self-isolating fans something to do.

That night, as I contemplated these ideas, I began to think about what I had done in the last three months – working with Warren and the Sydney Symphony Orchestra, planning and mounting a massive and incredibly complex Nick Cave exhibition with the Royal Danish Library, putting together the Stranger Than Kindness book, working on an updated edition of my “Collected Lyrics”, developing the show for the Ghosteen world tour (which, by the way, will be fucking mind-blowing if we ever get to do it!), working on a second B Sides and Rarities record and, of course, reading and writing The Red Hand Files. As I sat there in bed and reflected, another thought presented itself, clear and wondrous and humane –

Why is this the time to get creative?

Together we have stepped into history and are now living inside an event unprecedented in our lifetime. Every day the news provides us with dizzying information that a few weeks before would have been unthinkable. What deranged and divided us a month ago seems, at best, an embarrassment from an idle and privileged time. We have become eyewitnesses to a catastrophe that we are seeing unfold from the inside out. We are forced to isolate – to be vigilant, to be quiet, to watch and contemplate the possible implosion of our civilisation in real time. When we eventually step clear of this moment we will have discovered things about our leaders, our societal systems, our friends, our enemies and most of all, ourselves. We will know something of our resilience, our capacity for forgiveness, and our mutual vulnerability. Perhaps, it is a time to pay attention, to be mindful, to be observant.

As an artist, it feels inapt to miss this extraordinary moment. Suddenly, the acts of writing a novel, or a screenplay or a series of songs seem like indulgences from a bygone era. For me, this is not a time to be buried in the business of creating. It is a time to take a backseat and use this opportunity to reflect on exactly what our function is – what we, as artists, are for.

Saskia, there are other forms of engagement, open to us all. An email to a distant friend, a phone call to a parent or sibling, a kind word to a neighbour, a prayer for those working on the front lines. These simple gestures can bind the world together – throwing threads of love here and there, ultimately connecting us all – so that when we do emerge from this moment we are unified by compassion, humility and a greater dignity. Perhaps, we will also see the world through different eyes, with an awakened reverence for the wondrous thing that it is. This could, indeed, be the truest creative work of all.

Love, Nick x

Like Cave, Adorno too challenges us to ‘take a backseat and use this opportunity to reflect on exactly what our function is – what we, as artists, are for’ – and to lean into ‘other forms of engagement’ that such uncertain and time-altering times render (almost) unavoidable. It is certainly a time to consider our responsibility to and involvement in all kinds of violence, for example.

But is this the only or final word on the matter? Returning to Adorno and his book Minima Moralia: Reflections on Damaged Life, he suggests that:

The only philosophy which can be responsibly practiced in face of despair is the attempt to contemplate all things as they would present themselves from the standpoint of redemption. Knowledge has no light but that shed on the world by redemption: all else is reconstruction, mere technique. Perspectives must be fashioned that displace and estrange the world, reveal it to be, with its rifts and crevices, as indigent and distorted as it will appear one day in the messianic light. To gain such perspectives without velleity [fancy] or violence, entirely from felt contact with its objects – this alone is the task of thought.

Is not what might be true for ‘philosophy’ and ‘thought’ not also true for art? Redemption, the ‘messianic light’, exposes the incongruity between the world as it appears now and the world as it might be. That exposure – birthed and sustained by profound and counterintuitive hope, hope born not of trust in markets or in a change of conditions but which is the wholly unanticipated gift of the God of life – serves as both a judgement upon all that threatens and overcomes life, and as a promise that there is a love that is stronger than death.

That exposure also brings new possibilities for artists – in their freedom – to find their banjos, their pens, their brushes, their shoes, their voices, their humanity, etc. etc.

Human poiesis (and theology too, for that matter) can be – and in this world ought to be, as Jonathan Sacks put it in To Heal a Fractured World: The Ethics of Responsibility – a form of protest ‘against the world that is, in the name of the world that is not yet but ought to be’. It can like placing oneself right in the midst of a broken world – something like the way that the cellist Vedran Smailović placed himself in Sarajevo’s partially-bombed National Library in 1992 – and refusing to accept that the way things appear is the way that things must or will be.

℘℘℘℘

Two years ago, a friend asked me to make a sculptural piece for her dance company. All of us involved in New York City had limited means and space, as artists are pushed out of this-once art capital. As such, I began to create these shapes out of chicken wire mesh with tomato wire stakes as its armature (the garden), wrapped with electrical/lamp/cable wire (offering a gold leaf like light and hue). Eventually, I filled these voids with paintings of mine and/or crumbled up pages from discarded icon books, thinking of the “throw away culture” so poignantly revealed in Pope Francis’s Laudato Si and of my own attempts to rescue and to recycle these images.

Icons have traditionally employed metal coverings with stones and emeralds, Rizas, to protect the sacred image. Same here. Recently, I met a Ukrainian woman at my art opening who didn’t appreciate what I was doing with her tradition of sacred icons. Slowly, I walked her through my creative process and offered her the possibility that I was not only rescuing these images but liberating them from discarded books, bringing them out into the open. She nodded and had a change of view. As evidenced in Star, a light for us to follow in this Advent season.

Also brought to my attention by various strangers (this is why the viewer is so important in the visual arts) was the realization that these Riza sculptures which to me reveal the sacred icon image outside of book form, as well as my own renderings, were in the shadows – literally, cages – that echo the tragedy unfolding in my own USA, the dystopia of incarcerating immigrant adults, families and children.

℘℘℘℘

The religious historian Mircea Eliade wrote of the ‘eternal return’; the religious belief that liturgy and prayer can put the believer in touch with the ‘mythical age’, the time when the foundational events of their faith occurred. In the words of institution in the eucharist, we do not merely remember what Jesus said and did, we make his saving death and resurrection present to us now. We live in the mundane world where ordinary time passes, but there is another time – the ‘Great Time’ or Eternity that existed before the world began, that will exist after it ends and, moreover, that surrounds us now.

For Christians, our access to eternity is the person of Jesus Christ. He is our connection with God the Father. It is through Jesus that the Holy Spirit is sent to us. Our recurring prayer is ‘the Lord be with you’. Moreover, through Jesus we access all of Salvation History. Since he is the second person of the Trinity, he is present wherever the Holy Trinity is acting.

The first theologian to write of this was the Apologist, Justin Martyr, who died in 165CE. St Justin wrote in his Dialogue with Trypho of what we now call ‘Christophanies’ – manifestations of Christ in the Old Testament. He wrote:

Permit me, further, to show you from the book [sic] of Exodus how this same One, who is both Angel, and God, and Lord, and man, and who appeared in human form to Abraham and Isaac, appeared in a flame of fire from the bush, and conversed with Moses.

‘Angel’, which means ‘messenger’, is no longer a term we use with reference to the Lord Jesus, but Justin, with his understanding of Jesus as the visible manifestation of the godhead and the Word of the Father, reads the Exodus stories of messengers and voices as referring to Jesus.

Hence, when the Hebrew Scriptures refer to God creating through his word – ‘He spoke and they were made’ (Ps 33:9) – Christian commentators on the scriptures saw this as the Logos-Christos, the second person of the Trinity, in action. For the fourth day of creation, the Genesis text reads:

Then God said, ‘Let there be lights in the expanse of the heavens to separate the day from the night, and let them be for signs and for seasons and for days and years; and let them be for lights in the expanse of the heavens to give light on the earth’; and it was so. God made the two great lights, the greater light to govern the day, and the lesser light to govern the night; He made the stars also. God placed them in the expanse of the heavens to give light on the earth. (Gen 1:14–17)

For the strictly monotheistic Hebrews, it is the one God who set the lights of heaven. But the Church Fathers, reading the sacred text through the lenses of their Trinitarian faith, see the Word of God at work.

Christian artists charged with depicting eternity, creation, and heavenly things wanted to make it abundantly clear that their subject matter was in no way mundane, or earthly. The artistic convention that the icon tradition developed was to set their figures against a golden background. Unlike the earthly realm, the holy figures appeared amidst an even gleaming light.

Mosaicists achieved the effect by making glass tesserae with gold foil on one side. It was an expensive and complicated process, and it is amazing to see the huge extent to which it was employed in some of the great cathedrals of the world.

One such cathedral is that at Monreale, Cefalù, Sicily, Italy. It is one of the great masterpieces of the twelfth century. The ceiling, walls, and apse are ablaze with Byzantine icon-style images set in a field of gold. Still photographs do not do justice to the way the background changes as you move and as the light source alters.

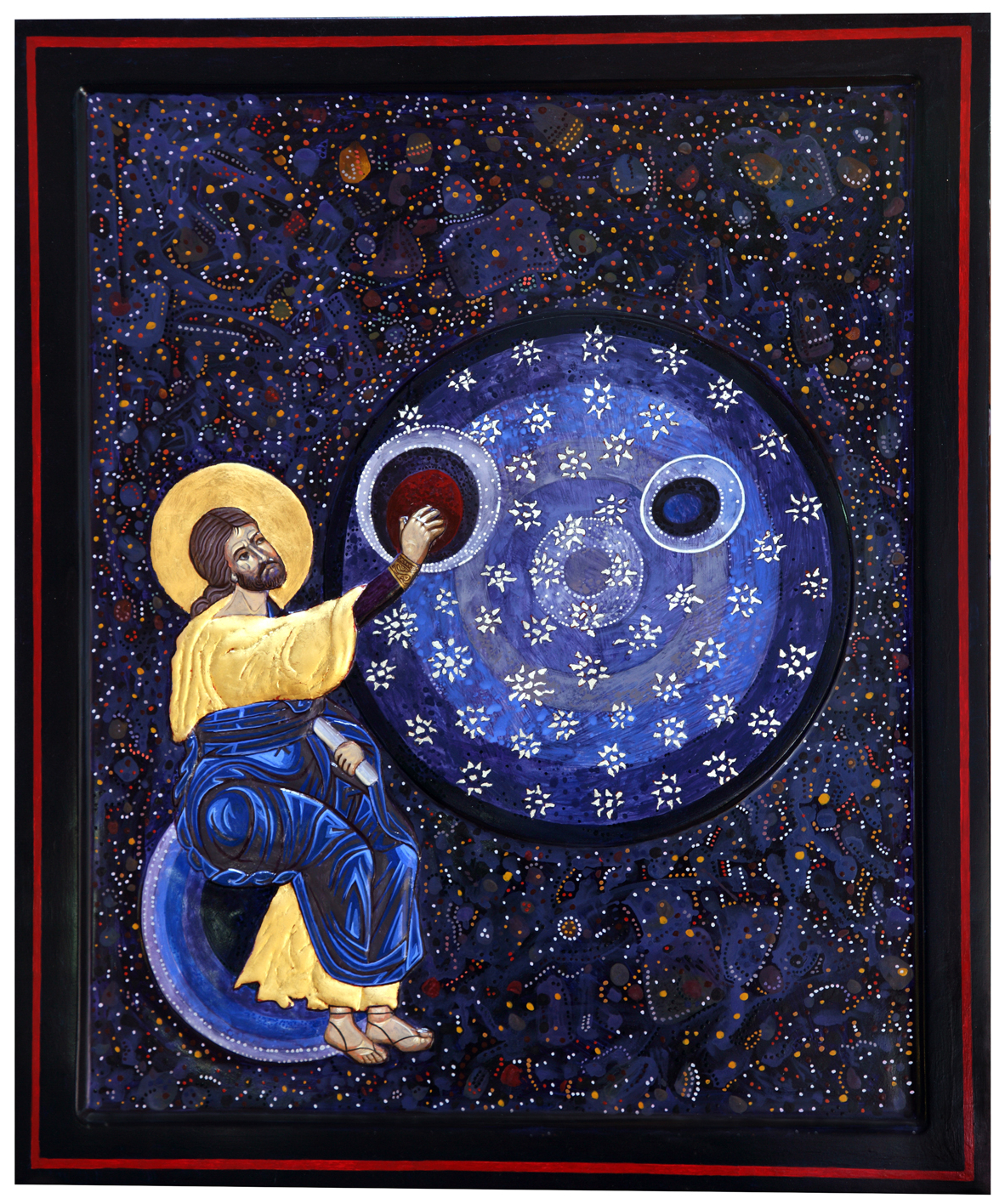

Monreale is the obvious influence on Michael Galovic. Icons influenced the mosaic of creation in the Cathedral, and now Galovic’s icon is a homage to that masterpiece. Given that he is working in a different medium, Galovic is remarkably faithful to his model. The circle of the heavens, the concentric shades of blue, even the placement of the stars is exact; though note that Galovic has omitted one particular star above the arm of the Christ. This could be a gesture of humility on the part of the artist – the disciple is less than the master – as well as an aesthetic choice to focus the interaction between the face of Christ and the light of the Sun.

The precision of the imitation adds impact to Galovic’s innovation. He, an expert at icon gilding, has taken away the gold of eternity and replaced it with something thoroughly Australian.

A common subject in Australian Aboriginal art is the Dreamtime, the time [sic] of the origins. A lizard may be depicted as the totemic ancestor figure who shaped the landscape. Dots, curves, and circles represent the Dreamtime before [sic] the mundane world came to be.

In Galovic’s icon, it is as if the Australian Dreamtime has replaced the Byzantine gold of eternity. His backdrop is more confused and chaotic than the gleaming tesserae of Monreale. There are dots, curves, the beginning of patterns, jumbled in an inchoate mass.

Galovic has not merely juxtaposed two artistic conventions, he has chosen a subject familiar to them both and he gives an authentically-Australian reading and re-writing of the Monreale mosaic. The ellipse that represents the moon in the mosaic is subtly dotted, alerting the viewer to how much this shape belongs to the ancient Australian artistic tradition as much as it does to the Byzantine culture.

Literally standing out from the background and distinct from creation is the figure of the Logos-Christos, seated on the cosmos (again outlined in subtle dots). Galovic has carved this figure in light relief from the same piece of wood which is the base of this icon. The halo is the only remaining gold and it is as if the newly-created sun is shining on the folds of the fabric of the over-garment. It is Jesus at work in creation, placing the sun in the circle of the heavens, and drawing us into the ‘eternal return’.

℘℘℘℘