Mandorla Art Award 2022. Theme: Metamorphosis (Isaiah 43.19)

In describing the winning artwork for this year’s Mandorla Art Award, the judges said:

The prophetic imagination invites us to lay aside old ways of being and sources of authority, and to imagine new futures.

Claire Beausein, who divides her time between Broome and regional Victoria, formed her work by stitching together over 600 wild silkworm chrysalises gathered from the wild in Indonesia. Chalice is a powerful work that draws you in close to experience the glorious sheen on the work and the lace effect of the shadow and to stand away from it and see the possible image of a face that some have described as the face of Christ. Claire began her exploration with thoughts of a shroud which symbolises the metamorphosis of the human person into eternal life. From there, her thoughts developed into a search for wild cocoons. The colour range is from gold to very pale yellow, and they are carefully patterned. Claire described the process of putting the artwork together as a meditative act. Some of the silk thread used to assemble this work is intentionally visible on the surface but much of it is hidden as is so much of our spiritual development. Our various spiritual metamorphoses in life are often hidden from sight but seen in effect and in our witness to what has occurred within. The work is suspended by museum pins, reminiscent of the moths and butterflies displayed as collections, standing away from the cotton rag paper background. The curved shape of the lower edge speaks of the shape of a chalice which holds the wine to be transformed and the gold colour also speaks of sacred vessels. Claire speaks of the ‘gravitas of profound change with the fragility of lace’. These opposites are in tension as in our spiritual lives.

Michael Iwanoff’s work, fromlittlethings, evokes the endless nature of change in all of creation, including within ourselves. He describes it as a ‘poetic meditation on the transformative seed each of us is able to sow into our awareness, experience and life’. The whole of creation is in the process of continual transformation, metamorphosis, as Paul says: ‘We know that the whole creation has been groaning in labour pains until now’ (Rom. 8.22). When the work of God is finished, when the whole of creation has been returned through the glory of Christ, we shall all be one in God. What is required is to wait in hope. In fromlittlethings the hope is symbolised by the seeds held in a small bag at the base of the painting, hanging from a mantle on which there is a small copper bowl from which water evaporates. There is so much in the work that is symbolic of all manner of change, some of which we are subjected to and some that naturally flows from our very nature. In the judges’ description, they spoke of the painting holding themes of ‘homecoming, journey, and acceptance’. There is a cosmological level too in the semblance of stars, and at different angles one catches a small glittery flash of light. In Michael’s description, he speaks of ‘this metamorphosis that is honoured and that so exquisitely grows the joy of being’.

Terre Verte, a particular green pigment, is revealed in the central section of Susan Roux’s free-hanging work. She begins her description with: ‘Adrift in rivers that divide and bind lands, I chart a home anew’. Susan’s original material for this work was a series of maps which symbolise the journey upon which she has personally embarked, and the journey of life that we all travel. The maps were washed and dried and stitched on a sewing machine using a completely free form of working the material. It is an extremely laborious way of building a fabric but the effect is rich and unpredictable. For Susan, it is also a deeply meditative way of working. There are structural wires inside that speaks of our own physical structure, our skeletal strength that is unseen but completely necessary for our embodied life. As the judges said:

Viewed from a distance the piece is reminiscent of a rock, geode, or even a distant universe, evoking an almost geological sense of time-scale and transformation.

Inside, however, the terre verte, the green thread used in free stitching on a material that is then washed off the stitching leaving a lace effect, is burgeoning forth. Life and creation continue in the green, growing heart of her work. This is the sense of Spirit, of re-creation, that Susan seeks. The metamorphosis marks many places in our journey. The great metamorphic actions in scripture include Abram’s journey west, the exodus from Egypt, the exile in Babylon and the return, and, of course, the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus. For Christians, there are many changes along the way, but the greatest is our baptism where we are changed into a new creation in Christ.

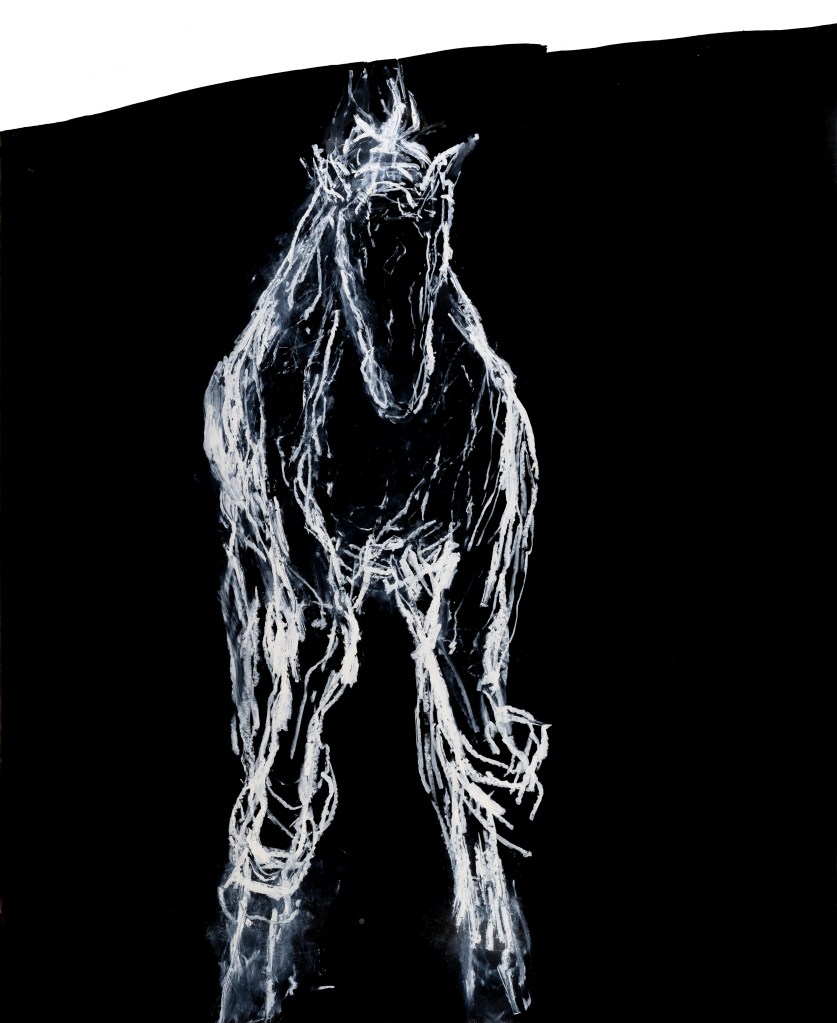

Angela Stewart’s artwork confronts you from the full distance across the gallery in the opening exhibition. There is a sense of compulsion and a desire to know the story. Her artist’s statement centres around grief, death, silence, love, loss, helplessness. Two years ago Angela’s son, a horseman, died. This artwork depicts the growth from out of the loss, the metamorphosis that grief insists upon. She will never be the same, but the horse is the symbol of the strength needed to get out of the depths of loss. It is a powerful work. In the Hebrew scriptures, the images of horses are important. If you had a horse, you went into battle with a better chance of survival than if you were on foot. In Psalm 33.17, however, we hear that the ‘war horse is a vain hope for victory, and by its great might it cannot save’. If we rely only on the things around us, the things we wrap our humanity and strength in, then we will not be rescued from our distress. It is these times that trust in the Lord is required and a time for us to move through the grief, as Angela says, to ‘recalibrate, begin, breathe, the horse, the rider, my son’. The judges’ comments say this succinctly:

The insistence of the image to be expressed captures the unstoppability of the prophetic voice – of the Divine voice – arising in unexpected places, disturbing and comforting, undeniable. This technically accomplished work plays with the inversion of light and dark, and evokes movement and disquiet with multiple images, ragged edges, and lines pulsing with energy.

The array of artworks for the 2022 Mandorla Art Award each offer us a way in which to view the theme of Metamorphosis – a profound or radical change. ‘I am about to do a new thing; now it springs forth, do you not perceive it?’ (Isaiah 43.19). In times of discontinuity, faith becomes an important ingredient, and this has been evident in times of radical change. With the pandemic, we have all experienced the need for change, and war and climate change continue to impact us all. Yes, we need to change and the challenge is to make it positive on the large scale as well as the small. The artists chosen as finalists gave expressions of metamorphosis that are both challenging and beautiful.

℘℘℘℘