Norman Franke is a New Zealand-based poet, artist, scholar, and documentary filmmaker. He has published widely on 18th-century literature, German-speaking exile literature, and eco-poetics.

℘℘℘℘

In many Christian communities, this time of year is known as Advent (from Latin adventus, ‘arrival’), the pre-Christmas season in which the birth of Jesus in Bethlehem is remembered and his eschatological reappearance, or ‘Second Coming’, is anticipated. A central element of the biblical Advent narratives is the annunciation, in which an angel prophesies to Mary that she will give life to the Son of the Highest. This is why the annunciation became a central theme in Christian visual art and in the music of many Christian cultures worldwide.

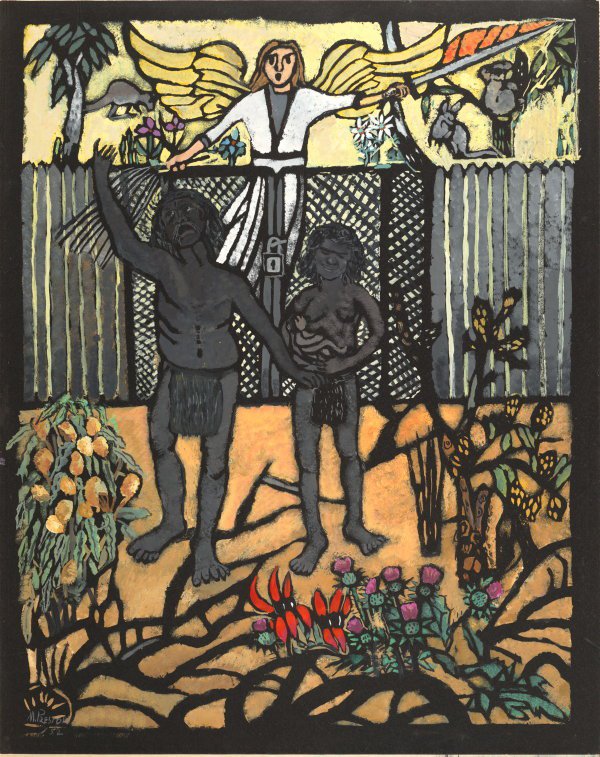

In this essay, I will revisit and contextualise Colin McCahon’s iconic painting The Angel of the Annunciation (1947). McCahon’s painting is also a helpful starting point for examining the dialogue between modern visual art in New Zealand and Christian theology, and between art and spirituality more generally.

I.

In his iconic painting, McCahon reclaims the old theological discourse of the Annunciation, the Lucan story of an angel telling Mary that she will be pregnant with the Son of God (Luke 1.26–38). In McCahon’s pairing, he has changed the setting from rural Bethlehem to rural Nelson, a creative act of adaptation and democratisation. Nelson, a visual topos that had been commissioned and aesthetically shaped for centuries by the religious establishment of institutionalised Northern Hemisphere Christianity, is transformed into a message for ordinary New Zealanders by an artist who was one of them.

In the late 1940s, when the painting was created, McCahon was little known to the public and the wider art world. New Zealand bourgeois audiences were shocked upon first seeing the painting. Yet, dumbfounded, too, were fellow artists such as the poet A. R. D. Fairburn, who expressed his bewilderment about McCahon’s takes on biblical scenes with scathing irony: ‘they might pass as graffiti on the walls of some celestial lavatory’.

For many viewers, McCahon’s The Angel of the Annunciation appears to be a predominantly religious and apolitical scene transposed into a New Zealand landscape: an angel announcing to a young woman that she will be pregnant and that her child is chosen to fulfil a divine plan. Yet for those who recall the words of the angel Gabriel in Luke’s story, the Annunciation clearly contains a theo-political message of chiliastic proportions as well, as the announced child will be ‘the Son of the Highest’ and ‘of his kingdom there shall be no end’ (1.32–33). As the angel of the Annunciation in Luke’s Gospel is explicitly concerned with theological ideas of political legitimacy and power, why would McCahon have wanted to reclaim the ancient Near Eastern theological ruler title (‘Son of the Most High’) and eschatology for his visual democratisation project in Aotearoa?

II.

To contextualise and better understand this problem, let us delve a little deeper into the visual theology and political theory that McCahon presents in his picture. McCahon depicts the announcement of arguably the most radical theological notion in history: the idea of God becoming fully human, the divine being embodied, becoming a compassionate social and political being. He shares human joy and pain in a solidarity that reflects the lived experience of human life in Roman-occupied Israel during the Second Temple period. He appears as a man (I’ll return to this), whom the angelic pronouncement names Yeshuah, Jesus, meaning ‘God saves’.

According to further scriptural records, in the Sermon on the Mount (equally in Luke’s ‘Sermon on the Plain’), the divinely human Yeshuah blessed the poor, the marginalised, the politically disenfranchised, and those who act as peace-makers. In his painting, McCahon alludes to this by depicting Mary and even the messenger (ángelos) as dressed and bearing themselves as ordinary, even indigent, humans. The mother of Christ, the ‘God-bearer’ – as Mary is sometimes referred to in Eastern Orthodox theology – is herself a young, somewhat destitute New Zealand woman in McCahon’s painting.

Thus, McCahon not only (re-)locates the Lucan dialogue between the angel and Mary in the Southern Hemisphere, but he also reclaims and renews central anthropological and socio-political elements of the Gospel. In his painting, the colours, gestures, and gazes McCahon employs are a translation of the biblical story back into their original socio-theological contexts. In Christian art history and theology, these contexts have often been neglected or reinterpreted in favour of images of triumphant angelic gestures and the lavish beauty and adornment of Mary as a God-bearer or Queen of Heaven.

III.

McCahon’s aesthetic language is a form of Expressionist Social Realism. Other modern European and American painters, such as Henry Ossawa Tanner, Paul Gauguin, Edvard Munch, and Walter Helbig, reworked the old topos of the Annunciation and returned it to a more original and authentic social setting. However, before McCahon visualised the Nativity in the Nelson hills, there was no such reclamation for the Southern Pacific, and no one, anywhere, with such a radical theological and artistic vision as McCahon.[1]

While there are allusions to famous Italian forerunners such as Signorelli and Fra Angelico (as in the angel’s half-profile and hand gestures), the meekness and ethereal sublimation of the Italian Renaissance painters’ versions of the Virgin Mary have disappeared in McCahon’s vision; with it disappeared the peculiar scholastic discourse on the ‘virginity’ of Mary, which most likely owes its origins to a misinterpretation of the Hebrew word almā (young woman), which in the Greek, partially Platonised texts of the New Testament is semantically restricted to parthenos, ‘virgin’.

IV.

Ever since the circulation of the Gospels, the more obvious, socially critical reading of Mary’s story – a single mother who finds herself in a most difficult social situation – has often been glossed over by Christian Mariology. In antiquity, numerous mythological narratives recounted the ‘immaculate conception’ of gods and political leaders, elevating them from the realm of the ordinary human to the divine. Legends of virgin births also exist concerning Alexander the Great, the Ptolemies, and some Roman Caesars. It is possible that Luke’s Annunciation story can also be read to either (metaphysically) surpass or critique the accounts of Roman dīvī (a political leader who becomes god).

However – and the avid Bible reader McCahon was clearly aware of this – the ‘pure handmaid’ Mary in Luke’s Gospel exhibits an unsuspected radical dimension. The biblical narrative of the Annunciation is followed by the Magnificat, Mary’s revolutionary song. It has inspired generations of visual artists, including Botticelli, James Tissot, and Maurice Denis; musicians who set the text to music; Northern Hemisphere composers such as Monteverdi, Bach, and Arvo Pärt; and New Zealand composers such as Ronald Tremain, Andrew Baldwin, and Janet Jennings.

V.

Arriving at her cousin and friend Elisabeth’s house, in the Magnificat, Mary proclaims: ‘(God) has cast down the mighty from their thrones/and has lifted up the humble./He has filled the hungry with good things,/and the rich He has sent away empty’ (Luke 1.51–53). McCahon’s down-to-earth interpretation of Mary’s revolutionary dimension is perhaps best illustrated by his use of colour and facial expression. Where the Renaissance masters clad the ‘virgin’ in precious (‘Marian’) blue, in ultramarine cloaks or the symbolic pink or red of motherhood and martyrdom, McCahon’s Mary wears earth-colours (with a hint of red mixed in), corresponding to the colour of the Tāhunanui landscape. He replaces the traditional authoritative habitus of the angel, facing the humble gaze of Mary, with an impenetrable, introverted yet subversive look. Mary’s eyes are shaded and painted in black[2] – a country girl dreaming of bringing down the rulers in a world gone crazy with autocrats and wars.

Focusing more on the human experience of a young woman than on metaphysically sublimated theology, McCahon makes the Annunciation’s message accessible to individuals of his own time and to modern New Zealanders through visual storytelling. In keeping with the addresses of the Sermon on the Plain, it is ordinary Kiwis – the commoner, the farm-hand, the every(wo)man – who are depicted and addressed in the work. Two ordinary women (the angel clearly displays female forms and goes barefoot) mark the beginning of an immanent and imminent history of salvation. Its starting point is an encounter on a country road (not in a study or a cella, as in traditional paintings).

VI.

According to Christian tradition, Jesus, the Christ, who the angel announces, is the New Adam, a novel universal man who overcomes the Adamic period of history since the ‘fall’ in paradise – a period in human history marked by trespasses, conflict, and sin. In McCahon’s painting, there is little evidence of this grand salvation scheme. However, by (socially) democratising the divine in the context of a New Zealand rural scene of two women meeting in the Nelson hills, one of them pregnant, the artist reclaims two other theological notions foundational to Judeo-Christian notions of religious democratisation.

Firstly, the genesis of new human life in McCahon’s painting alludes to the imago dei (image of God) passage in Genesis 1.27 (‘So God created humankind in their own image, in the image of God he created them; male and female he created them’.) The word for God in this ancient Hebrew text is Elohim, an old plural term, suggesting diversity within the deity. In some forms of its Christian reception, the old imago dei theology, which has also inspired the United Nations’ Declaration of Human Rights, is connected to the theology of Corpus Christi (the body of Christ). Mary’s giving birth to the human God also marks the beginning of the mystical notion of a collective, liberating divine Being of which all humans are part. They all participate in their effort to bring about the world’s salvation.

Notions of a mystical collective body, the ‘body political’, the corporate body, or the corporation (Lat. corporare, ‘combine in one body’) have been appropriated by many political and economic organisations and ideologies throughout history. Still, they have also continued to inspire social movements and social revolutionaries, both religious and secular. In McCahon’s painting, the Annunciation’s ‘kingdom’ of God, referring to Luke’s kingdom of God, which paraphrases and connects with older Hebrew concepts of the Maləchūt haʾElohīm, assumes a down-to-earth and pluralistic dimension. On earth as in heaven, McCahon seems to suggest, the kingdom is closely related to the life and hopes of ordinary people. It is not a feudal, hierarchical, or otherworldly power construct, but is immanently inherent in the solidarity of encounters and communication among ordinary people.

By democratising salvation history and opening it up to a social-realist Corpus Christi theology, McCahon also presents the role of women in a new, more active form than in the traditional imagery of many churches. In McCahon’s portrait of the two women, the creator Elohim’s female dimension (‘as men and women, he created them’) comes to the fore. It is a comprehensive and inclusive salvation history that we see in the painting of McCahon, who was an active pacifist, advocate of social justice, and who had close links to the Society of Friends (Quakers), who traditionally address every fellow human (even their enemies and persecutors) as ‘friend’.

Secondly, with his two female figures in a New Zealand landscape, McCahon – who in many other paintings engages with biblical words and discourses – points in his Annunciation to people and the material world as sources of life and collaborators of salvation: The Word made flesh, in and through humans (John 1.14).

It was the Jewish philosopher Hannah Arendt who, in her groundbreaking philosophical writings after the Second World War, observed that throughout the centuries, Western, male-dominated anthropology, ethics, and theology had a fixation with death and mortality. Memento mori, ethics and aesthetics, life as a ‘sickness until death’ (Kierkegaard), and even large parts of Christian theologies of the cross are examples of discourses centred on the end of life and the breakdown of all human communication and meaning through death. Arendt did not deny the gravity of human finitude, vulnerability, and mortality, nor the ethical and social implications thereof. She argued, however, that Western philosophy exhibits tendencies toward a morbid fascination with the end and the heroisation of death, which is entirely unbalanced by the other pole and dimension of life: to be born and to be born anew. This female-connoted, life-giving and life-affirming force – humanity as born into the world ‘in the flesh’, the realisation that every person is born of a human mother – has long been overlooked, marginalised, and oppressed by dominant theological and philosophical discourses. For Arendt, being born, Geburtlichkeit or natality, together with physically emerging into concrete geographical and social spaces, is the ever-new beginning of human communication and acting (Kommunikation und Handeln), of individual and collective potencies to reshape and reform the world. As Arendt recognised in The Origins of Totalitarianism, ‘with each birth, a new beginning is born into the world, a new world has potentially come into being’. Similarly, in 1966 McCahon submitted: ‘Angels can herald beginnings’. For both Arendt and McCahon, the ethical and creative potential of each birth is integrated into a wider trajectory of the salvation of the world. So, Arendt, in The Human Condition: ‘The miracle that saves the world, the realm of human affairs, … is ultimately the fact of natality, in which the faculty of action is ontologically rooted’.

VII.

This may be why Christmas has long been the most widely observed of the major Christian holidays and why depictions of the Nativity are so prevalent. The (archetypal) nature of the birth of a new human as a personal, social, and cosmological event resonates with so many people, for all humans were born into the world. Christmas is arguably more accessible and familiar than the more theologically and religiously focused holidays of Easter and Pentecost. In the encounter of two earth-toned female figures in a landscape of Aotearoa, McCahon anticipates the Nativity. Given his profound interest in Māoritanga, McCahon would have understood that the Māori word whenua (land, ground) can also assume the meaning ‘placenta’ and is therefore closely related to birth and birth-giving. The whenua is a prerequisite and incubator for human life and growth, carrying both material and spiritual connotations. Incidentally, the Latin-based English words ‘nature’ and ‘matter’ (as in materiality) offer a similar, if largely forgotten, etymological outlook: nature derives from nasci (to be born), and matter is linked to mater (mother), not just as a nourishing substance but as a caring being.

For all its terrestrial groundedness, the Annunciation painting also possesses a loftier, linguistic and spiritual dimension that connects it to many of McCahon’s later word paintings. In the Annunciation, McCahon’s angel is both running on the ground and hovering; like language itself, the angelic message is both spirit and matter. Until the large formats of his late work, McCahon’s focus is on religious words, on announcements, annunciations, and promises, on divine speech acts – often together with the question of whether God’s biblical promises have been fulfilled or can be fulfilled.

A recurring theme in McCahon’s work is the question of whether God saved his son from death, whether the Christ truly rose from the dead, and, by extension, whether a benevolent God who can ultimately overcome the destructiveness of world history exists. This question becomes increasingly urgent and existential for the artist toward the end of his life. The question of whether the most subtle and profound religious speech act, the promise of ultimate redemption of the world, in the end times, in immanent and metaphysical dimensions, can be trusted, requires more and more faith. While the end of (salvation) history remains open to speculation, conjecture, and belief, its beginning seems more precise and more concrete. The Annunciation angel’s simple promise of new life has already been fulfilled. God continues to be revealed in human life across many regions of the world, including the Nelson Hills.

* I would like to thank my old friend Rev Keith Ross for giving his time, insight, advice, and different views. The errors are mine.

[1] McCahon’s contemporary, James K. Baxter, worked on a similar project in the literary field, transposing the Christian (social) message into everyday New Zealand life. A more detailed comparative analysis of their theologies would be worthwhile. However, unlike McCahon, Baxter, who fell from grace through the recent publication of personal documents, had arguably a more reactionary view of women. The daughter of an Anglican Archdeacon, Anne McCahon, Colin’s wife, was also an artist. She collaborated with him on some of their earlier works, was his most important critic and advisor, and, in 1947, was pregnant with their fourth child. Without her, McCahon could not have created his work. For a nuanced assessment of her role, see Frances Morton’s essay, ‘The Power of Two: The Woman Behind Colin McCahon’.

[2] Traditionally, European paintings focused on one or more of these aspects: conturbatio – Mary’s excitement regarding the shocking message; cogitatio – her reflection on what has been announced; interrogatio – her inspection of the message; humiliatio – Mary’s submission to God’s plan; meritatio – emphasis on Mary’s merit. In McCahon’s treatment, these dimensions are not dominant, nor are they totally absent.

℘℘℘℘