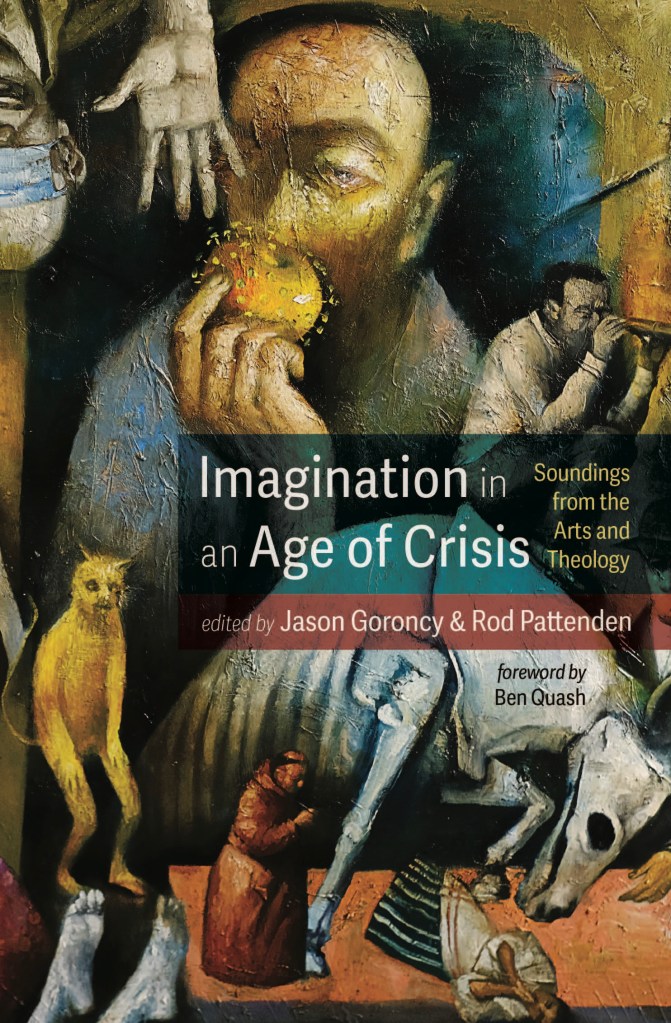

Review of Imagination in an Age of Crisis: Soundings from the Arts and Theology, edited by Jason A. Goroncy and Rod Pattenden. Review by Dr Angela McCarthy.

This is a book that one can dip in and out of many times, and the gift still keeps giving. Poets, writers, musicians, artists, journalists, and others have contributed to this volume, which makes it very rich, and this book review cannot cover all the richness. Some of the contributions are short, and others lengthy.

Trevor Hart’s contribution, ‘Why Imagination Matters’, declares that the presumption behind this book is that imagination certainly matters, particularly in times of crisis, including the COVID pandemic, war, and climate change. Imagination does not only matter to artists, although their work is bound to the imagination. In times of crisis, scientists, medical professionals, bureaucrats, and many others also bring imagination to problem-solving so that the result can benefit society.

Lyn McCredden, in writing ‘Imagination and the Sacred’, explores ‘the sacred’ as a sense of reality that embraces the places and times where individuals and communities encounter meaning. Australian secularism decries the need for religion for moral or social benefits, but in examining literature post-1950, McCredden delineates the presence of ‘the sacred’ being firmly present. She uses the experience of Nick Cave, a contemporary musician who has suffered and shared his profound and personal grief, and how he links his pain in growing to know the impermanence of things with illumination. The pain helped him enter into the transcendent, and McCredden links that to the experience of Patrick White. These are powerful connections being made within Australian culture.

Libby Byrne looks at the reality of being a professional artist and what that means to herself and those who encounter her works. She briefly reviews the artist’s place in society over time and culture to show that the postmodern artist is part of a set of shifting identities. In the past, the artist did not often sign their work as it was done for ‘the glory of God’ at the behest of a religious institution. Now, the artist’s identity in the public space has a completely different social and economic relationship. Byrne dwells on the Brooklyn Art Library’s collection of 50,000 artist sketchbooks and what it means to be included in such a collection in the public sphere.

Trish Watts, in ‘Every Life Can Sing’, describes her experience in Cambodia, where she sought to help the people who had lost their songlines because of the oppression suffered under the regime of Pol Pot. Watts is a professional singer and Voice Movement Therapy practitioner and accepted the challenge to help rebuild the voice of the people. Only fragments of the culture were left because ninety per cent of the artists, musicians, teachers, doctors, and other professionals had been eradicated. To rebuild the voice and the imagination that could once again voice hope in a crushed country is indeed a healing experience.

Steve Bevis writes about Ida Nangala Granites, a senior Warlpiri woman caught between the two worlds of Alice Springs and her home country of Yuendumu in the Tanami Desert. Ida re-enacts her truth, her participation in her Dreaming, through her paintings. Everything in her paintings is symbolic. She paints within the same reality as her ancestors; everything is expressed through the symbolism of who she is in her country. Ida is economically marginalised and sometimes cannot afford art materials. However, in this crisis and through her imagination, she helps others see and grow in understanding of her country and people.

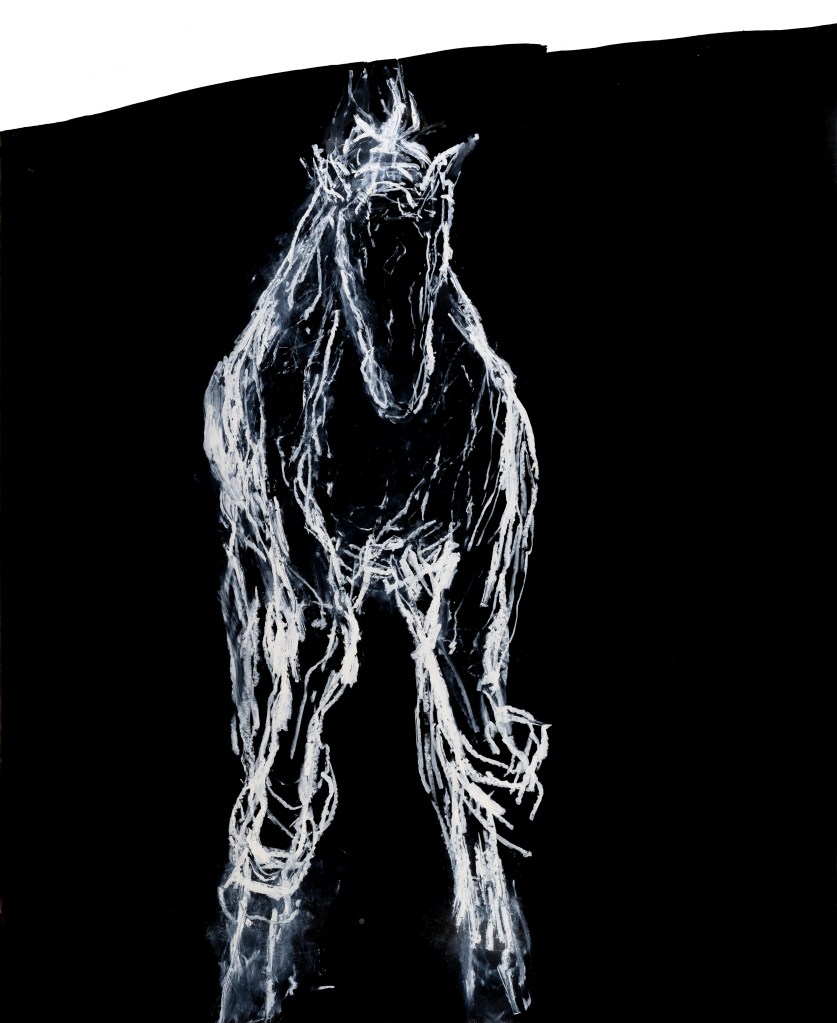

Rod Pattenden writes about the art of George Gittoes, setting his commentary on the return of the arts to a socially and ethically responsible realm. For much of the twentieth century, art focussed on what is fashionable and avant-garde in an economy dominated ruthlessly in some places by art critics. In a world where horror images and violence dominate and intend to unsettle our society, art is needed in the action of social renewal and ethical behaviour. War and climate change have certainly exposed the need for seers. Pattenden has long worked with George Gittoes and has valuable access to his methods, art, and capacity to use his imagination in conflict areas. He can show how Gittoes can be seen as a prophet and mystic in his ‘role that values actions towards provoking awareness, creating change, and offering hope in social contexts’.

This collection of writings ranges in depth and focus to bring a richness of cultural awareness and imaginative power that brings hope and value to our culture through the interactions and power of artists.

℘℘℘℘